Decompiling Hyper-V Manager to rebuild it from source

Why Hyper-V Manager?

Hyper-V is undeniably a critical component of the Microsoft virtualization stack as Azure runs on it, but it's also used in Virtualization-Based Security, Windows Containers, Windows Subsystem for Linux, Windows Subsystem for Android, and even the Xbox.

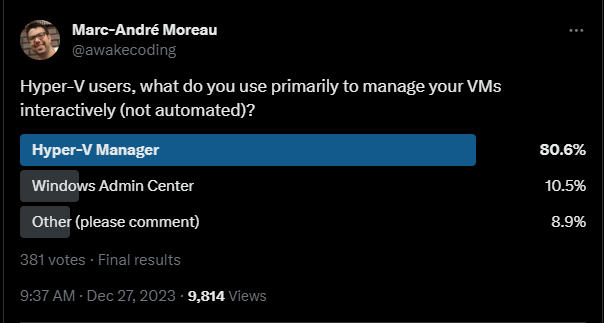

Then comes the "regular" Hyper-V virtual machines, for which Hyper-V Manager is the most popular management user interface today, far ahead of Windows Admin Center:

In theory, Hyper-V Manager has been replaced by Windows Admin Center, but for most users out there, switching to a localhost web application with self-signed certificates feels like a major downgrade. At a bare minimum, wrapping Windows Admin Center in a WebView2 "desktop" application could help alleviate some of the adoption problems.

The Hyper-V PowerShell cmdlets that wrap the underlying Hyper-V WMI provider are well maintained and provide complete access to many settings not properly exposed in Hyper-V Manager. However, while PowerShell is great for automation, nobody really wants to manually type in Set-VMProcessor -VMName <VMName> -ExposeVirtualizationExtensions $true to enable nested virtualization in a virtual machine: a simple check box in the user interface would be much faster for the same operation.

Here's the problem: while Microsoft thinks Windows Admin Center replaced Hyper-V Manager, the reality is that it hasn't. Hyper-V Manager, despite being used by 80%, is considered "legacy" on life support. It receives no improvements, despite its pain points being very well known by the community of IT professionals using it. Improvements in Windows Admin Center have limited effect due to its relatively low adoption.

I have one wish for 2024: that Microsoft open sources Hyper-V Manager such that the community can freely improve it.

I, for one, would like to champion such an effort. Hyper-V Manager is a mature product with a large number of users with a long list of relative minor improvements or fixes that would make a huge difference. Rewriting Hyper-V Manager is hard, as Hyper-V has a lot of advanced features which most users don't touch unless they're running a production Hyper-V environment. This being said, the most promising open-source Hyper-V Manager alternative right now is VMPlex Workstation. It is written in WPF and uses a clever trick to load the same configuration dialogs and wizards as the original Hyper-V Manager. Ideally, they would all have to be rewritten, but this makes it functional from day one.

Why Bother Decompiling?

Hyper-V Manager is written in C# using WinForms, and while it still targets .NET Framework and is designed to be hosted in mmc.exe, it is exactly the type of application that can decompile well enough to be built from source again. Automatic .NET decompilation of external code is so common that even the latest version of Visual Studio does it by default. However, one should understand that decompiled code is not open source code: it doesn't have the proper legal status granted by an open source license and is therefore not suitable for an open source project.

The primary goal of decompiling Hyper-V Manager is really to assess its value as a potential open source project, which is what I'm hoping Microsoft can be convinced to do. Microsoft has its eyes on Windows Admin Center and has been leaving Hyper-V Manager to die a slow death. I think Hyper-V Manager deserves a better ending with a community-lead project.

The secondary goal of decompiling a complete .NET application like Hyper-V Manager to rebuild it from source is really the educational value of the exercise. We've all experimented with .NET decompilation in the past one way or another, but very few have tried really going all the way to reconstruct a complete solution with individual projects that can be built from source again in Visual Studio. Yes, it is possible to patch .NET assemblies, but building the entire program from decompiled source code makes certain kind of changes possible.

Installing Required Tooling

Install the .NET SDK and make sure the dotnet CLI works, as we'll use it to create and edit solution files. I will be using Visual Studio to build the project, but feel free to use any suitable alternative.

For scripting, we'll be using PowerShell 7. I recommend using VSCode for editing and Windows Terminal to run the scripts.

For .NET decompilation, open an elevated shell and install ILSpy GUI and command-line tool:

dotnet tool install ilspycmd -g

winget install icsharpcode.ILSpy

For blazing fast textual search and replace from the command-line, install RipGrep:

winget install BurntSushi.ripgrep.MSVC

You will also want a good text editor that can do fast textual (no IntelliSense please!) search in a directory. Sublime Text is a good choice if VScode is not your thing.

During our analysis, tools like Process Monitor and Process Explorer will come in handy:

winget install Microsoft.Sysinternals.ProcessMonitor

winget install Microsoft.Sysinternals.ProcessExplorer

You will also need the git command-line tools, and a simple git GUI to view the history of commits like gitk that usually comes built-in:

winget install Git.Git

Last but not least, ChatGPT as your assistant - it's really good at generating PowerShell code snippets and even regular expressions. I also recommend regex101 to help visualize regex to get it right instead of just guessing it.

Finding Assemblies of Interest

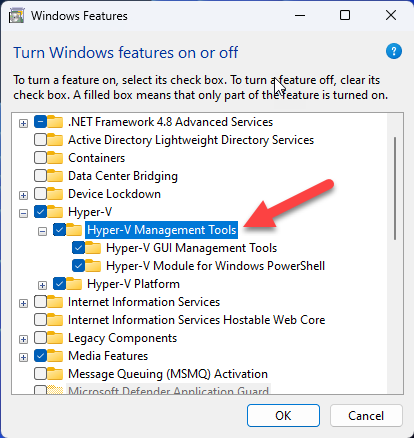

Our target is Hyper-V Manager, which can be installed by enabling the Hyper-V Management Tools in Windows. Note that you can use a VM without nested virtualization for this part, since the management tools can be installed without the virtualization host features:

Enable-WindowsOptionalFeature -Online -FeatureName Microsoft-Hyper-V-Tools-All

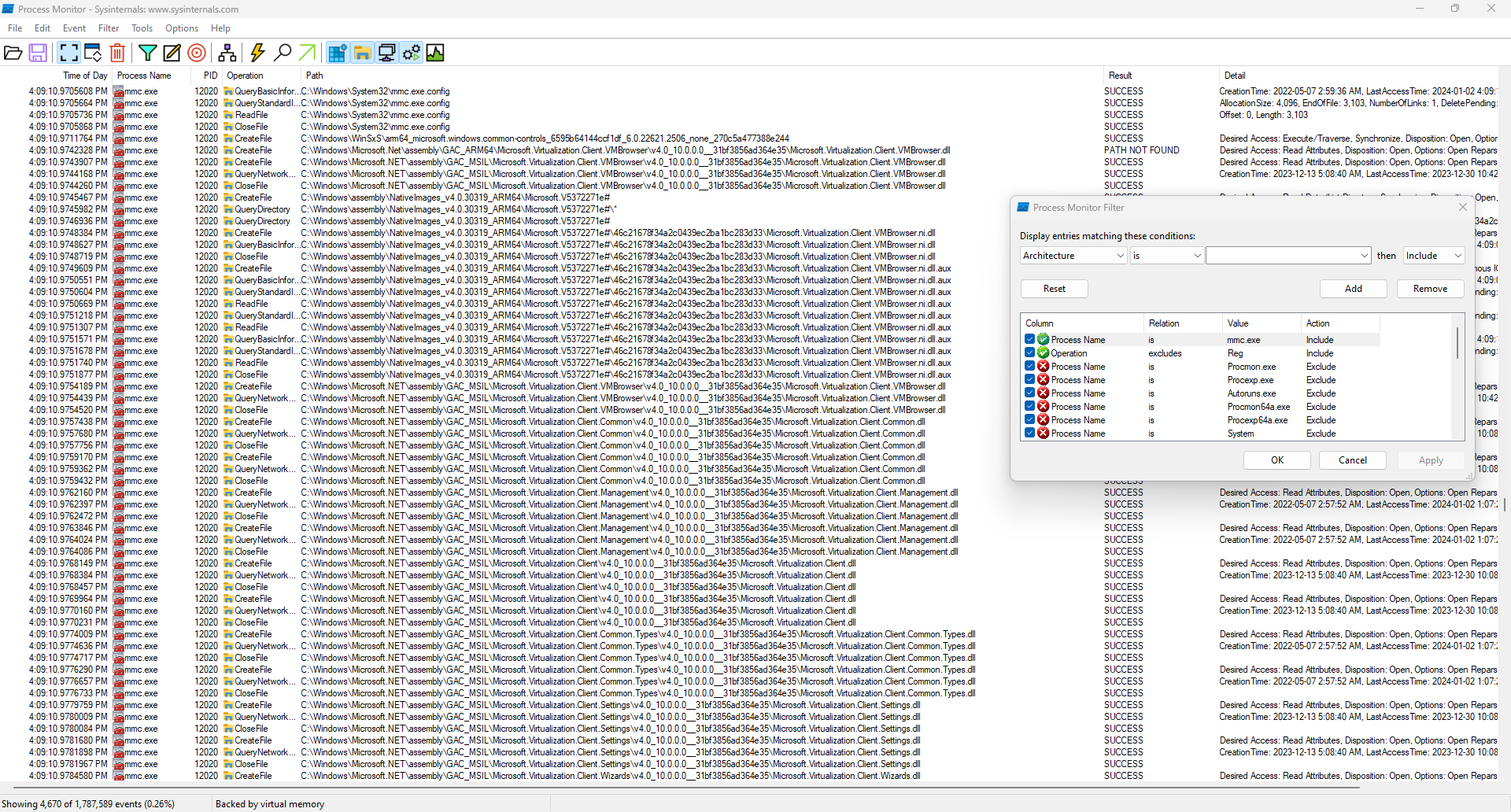

Launch Process Monitor (procexp) with the following filters:

| Column | Relation | Value | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Name | is | mmc.exe | Include |

| Operation | excludes | Reg | Include |

From the Windows start menu, search and launch "Hyper-V Manager". In Process Monitor, scroll down until you find some file operation that looks like something interesting. Unfortunately, we seem to be hitting cached assembly files, and we have no idea where the original ones are.

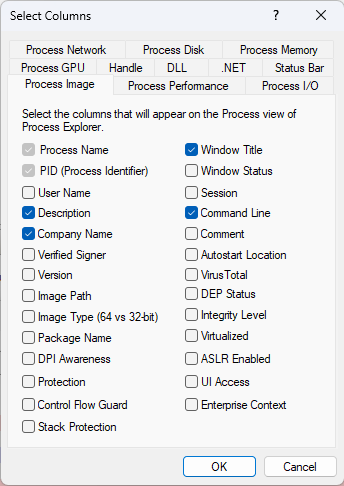

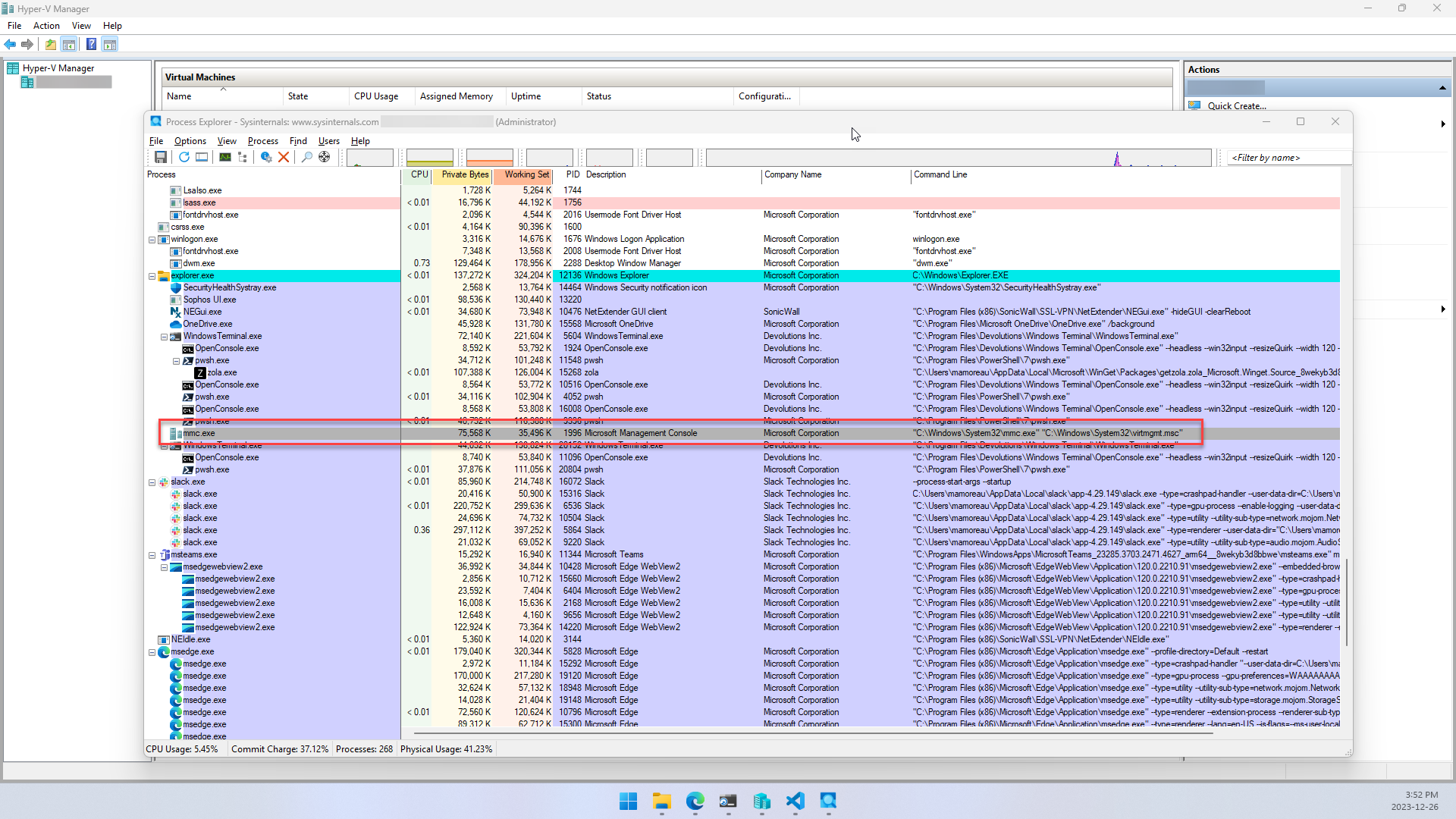

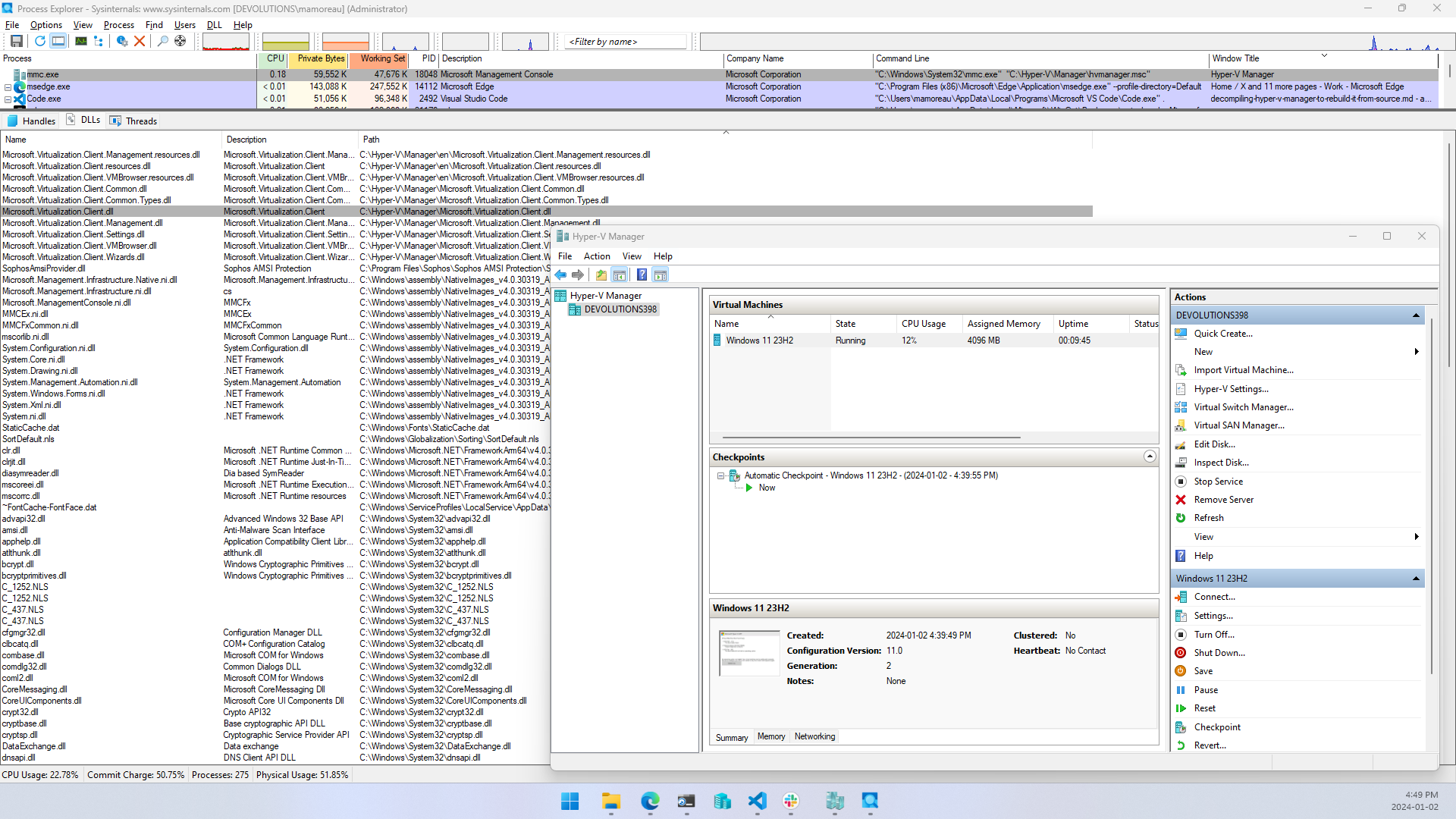

Launch Process Explorer (procexp) as an administrator. Right-click on one of the columns in Process Explorer, then click Select Columns, then select Window Title and Command Line:

Find the process that has the "Hyper-V Manager" window title. If you can't find it, then Process Explorer was most likely launched without elevation.

Let's now look at the command line behind Hyper-V Manager:

"C:\Windows\System32\mmc.exe" "C:\Windows\System32\virtmgmt.msc"

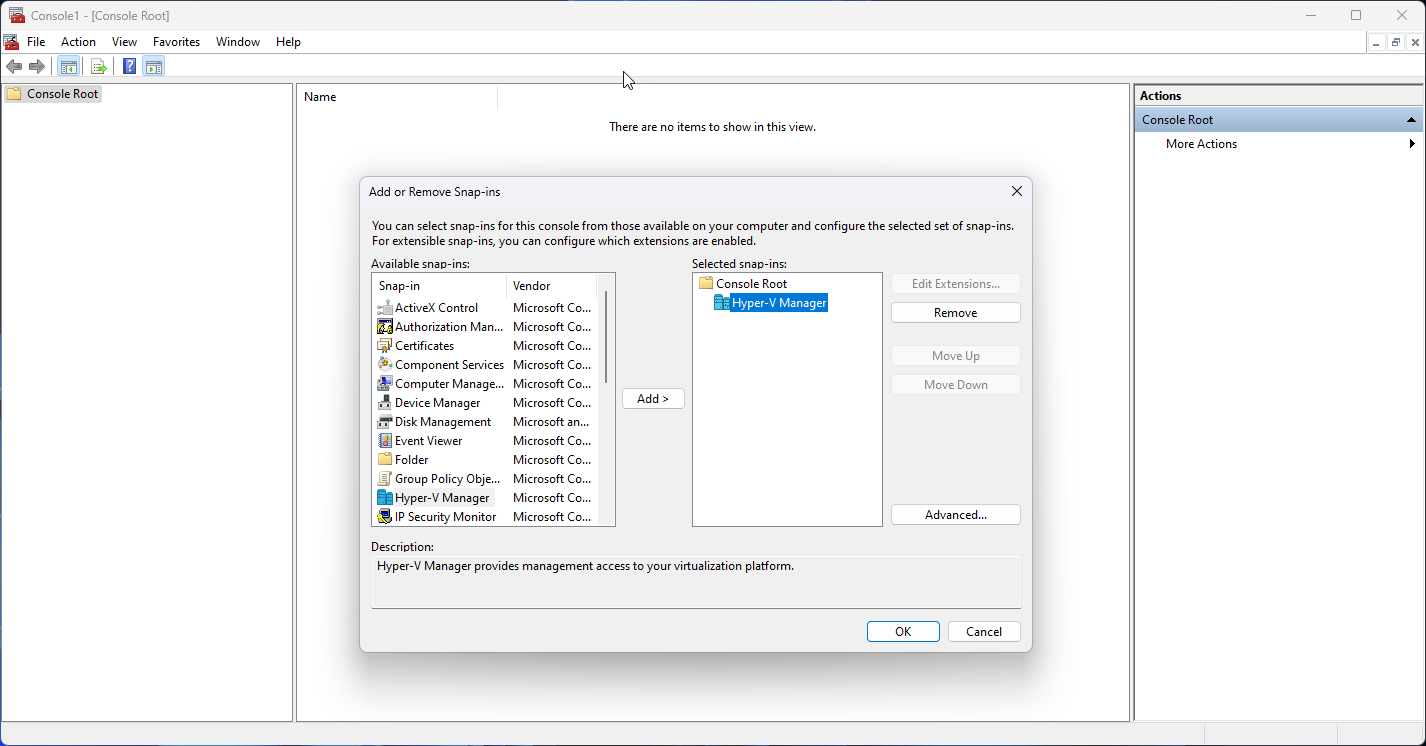

What does it mean? With a bit of research, we can figure out that Hyper-V Manager is a Microsoft Management Console (MMC) snap-in, and the virtmgmt.msc file is the specific management console to load. If we launch mmc.exe directly, we can manually add Hyper-V Manager to a generic management console instead:

This complicates our search a little bit, since mmc.exe is a generic executable that loads specialized management consoles like Hyper-V Manager. We still don't know where the assemblies or interest are located. Let's open virtmgmt.msc in notepad to see if we can find out more:

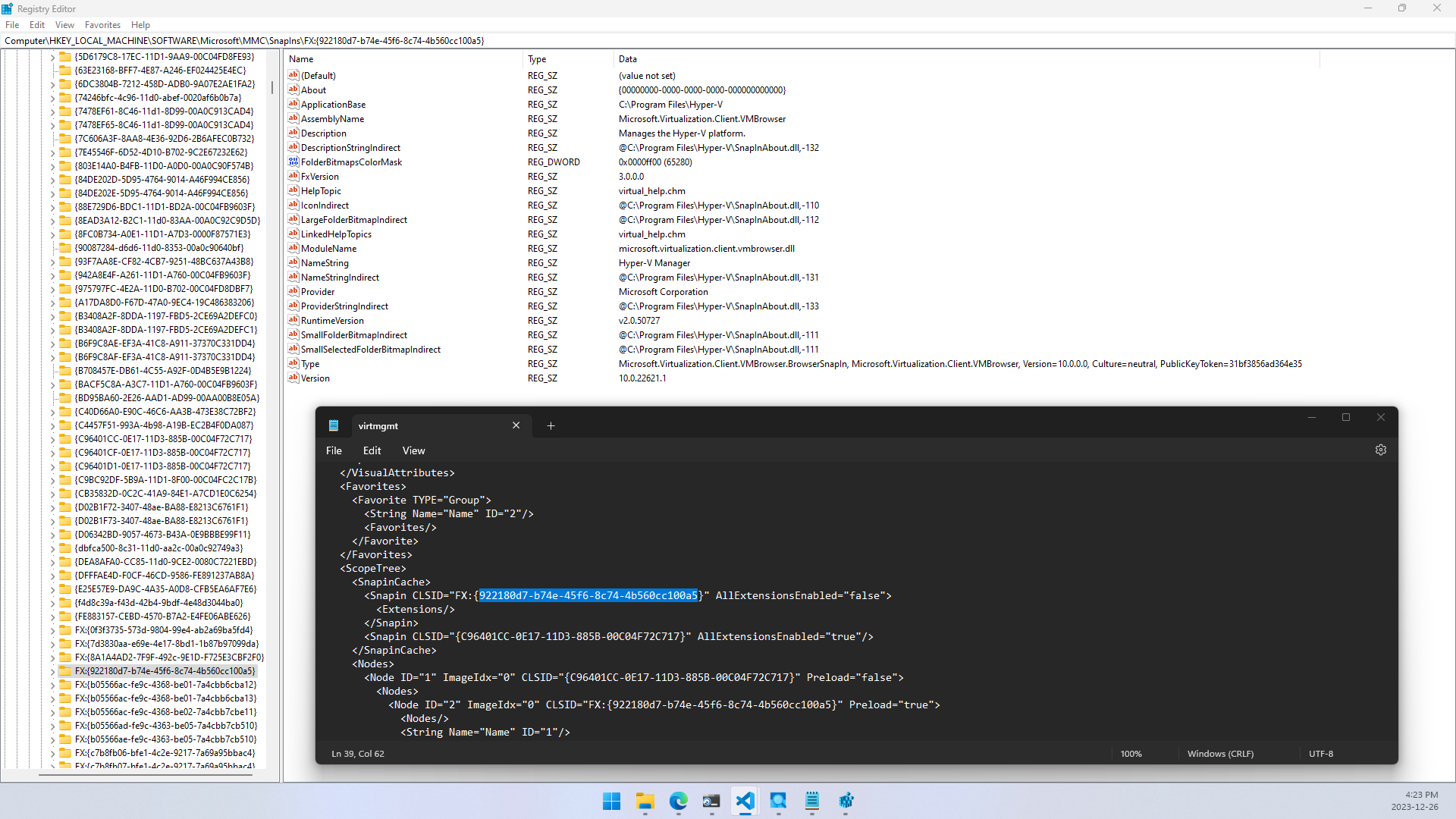

Thankfully, virtmgmt.msc is an XML definition file, and it contains what looks like a COM class id. By searching in the registry for the same id, we have a hit under [HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\MMC\SnapIns\FX:{922180d7-b74e-45f6-8c74-4b560cc100a5}]. By looking at the registry keys, we find that "C:\Program Files\Hyper-V" is the application base path:

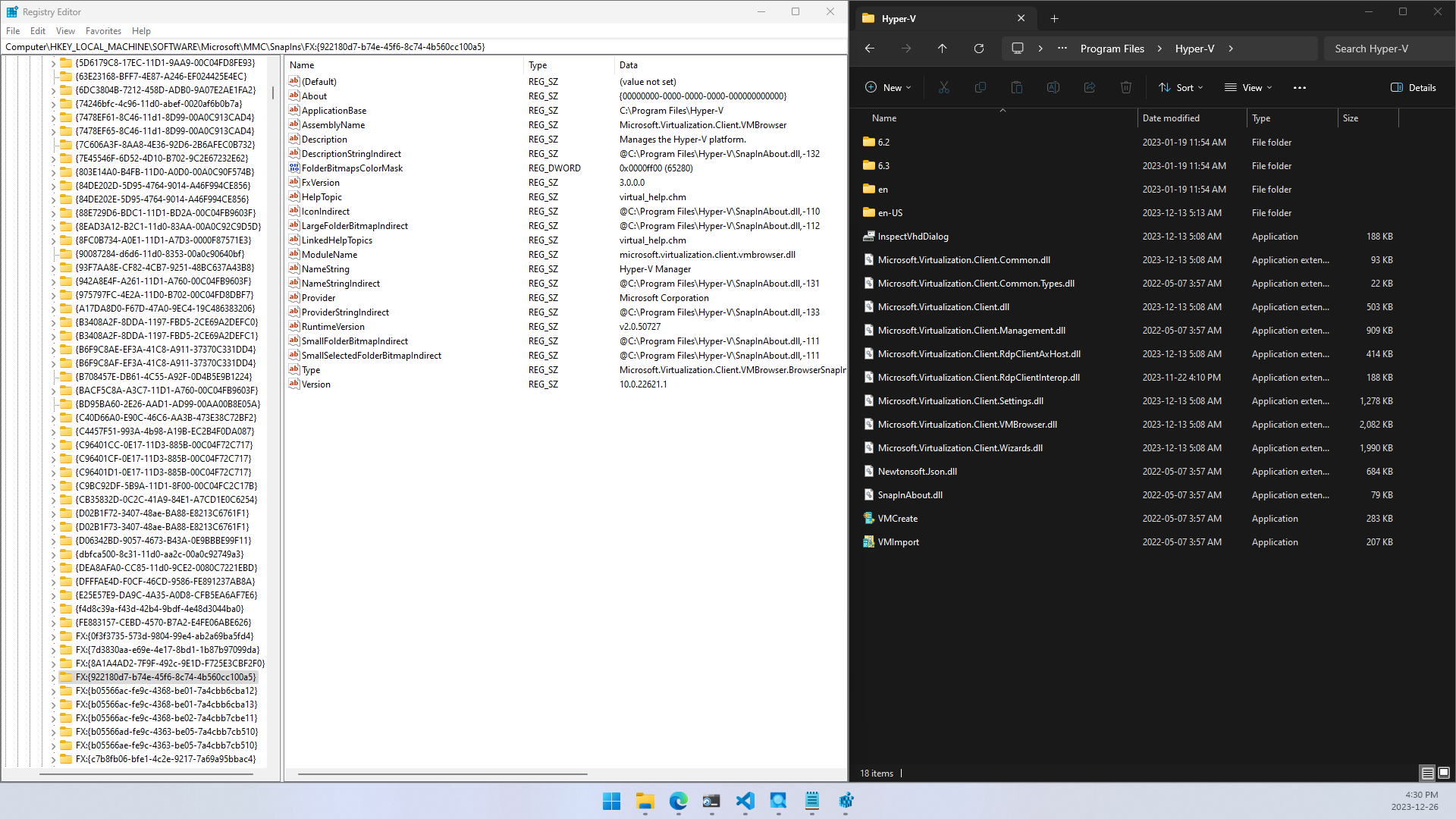

Bingo, we finally have our files! Create a zip file of the entire Hyper-V directory as a backup for now. Using regedit, export the registry keys we've found to virtmgmt.reg, as they could be useful later.

A word of caution on trying to patch the original Hyper-V Manager located in %ProgramFiles%\Hyper-V: don't do it. This is what I originally tried, and thought I was successful until I realized using Process Explorer that the DLLs from the global assembly cache were loaded instead, and they can't be removed without uninstalling Hyper-V Manager. Even if you do this, you will need to purge the native image cache as well. For this reason, it is much simpler to use a different COM class ID and register our custom Hyper-V Manager in a different location.

Initial Analysis of Decompilation Target

Create a workspace for the reversing project. In my case, I copied the contents of "C:\Program Files\Hyper-V" to "~\Documents\Reversing\Hyper-V". Let's start with the easy stuff: mmc.exe loads snap-ins, which are library components, not executables, yet we see executables:

- InspectVhdDialog.exe

- VMCreate.exe

- VMImport.exe

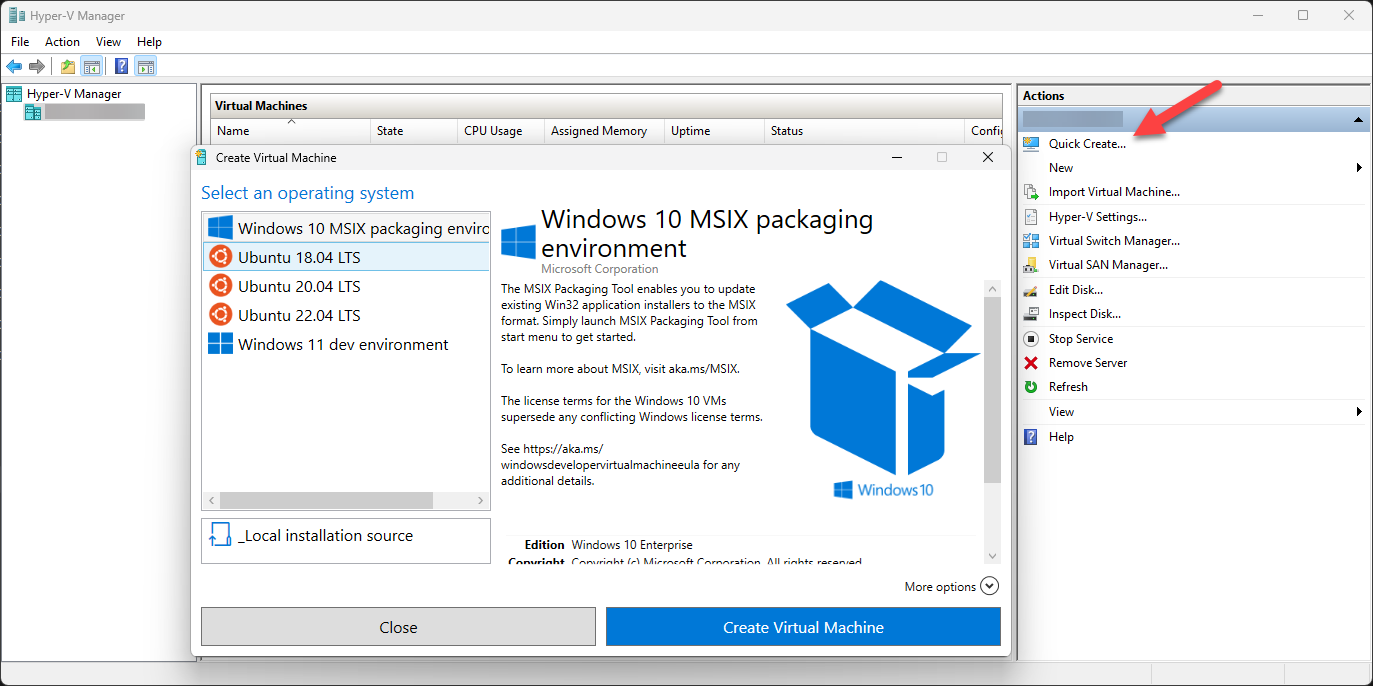

By launching them directly, we realize that VMCreate.exe is just a helper executable launched from Hyper-V Manager for the Quick Create feature:

We can guess that VMImport.exe and InspectVhdDialog.exe serve similar purposes. Since they are external executables, they can be built separately from the core assemblies of interest, so they can be safely scoped out at this point.

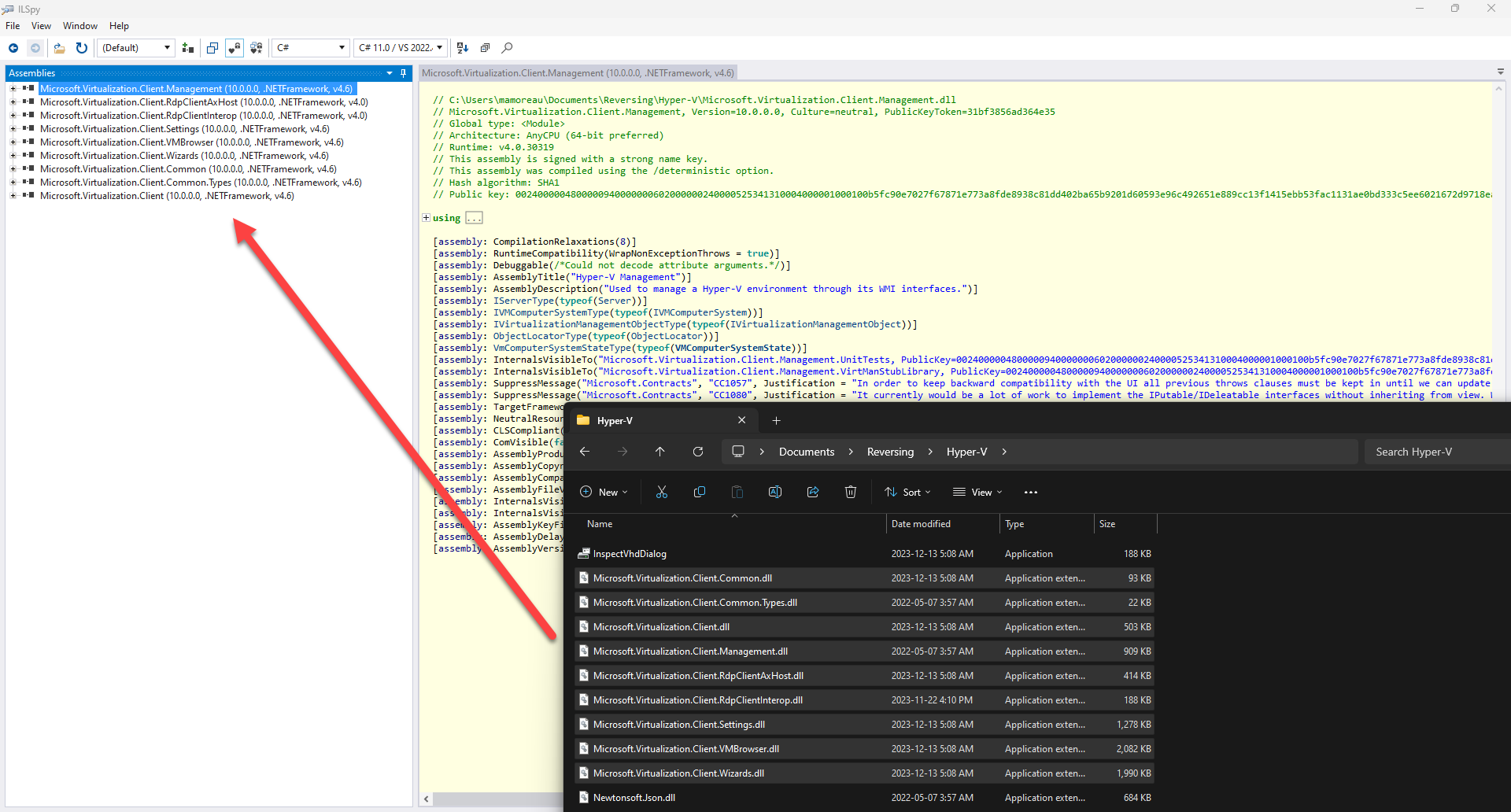

Now for the fun part you've been waiting for: launch ILSpy, then drag all the DLLs that begin with Microsoft.Virtualization.Client into it:

Why Microsoft.Virtualization.Client? Because it looks like the assembly namespace used for Hyper-V Manager internally. Newtonsoft.Json.dll is a common dependency of low interest. As for SnapInAbout.dll, it is not even .NET - it's a native library that appears used only for the MMC snap-in registration, so let's put it aside.

From a quick look at the information provided by ILSpy, most assemblies target .NET Framework 4.6 (!) but two assemblies (Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.RdpClientAxHost.dll, Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.RdpClientInterop.dll) target .NET Framework 4.0 instead, which is so both old and odd:

It takes a bit more work to figure this one out, but those two assemblies are in fact generated .NET Interop DLLs for the RDP ActiveX control interface. Those are probably needed for the Hyper-V Manager special RDP client, vmconnect.exe, which is currently missing from our decompilation project. Let's unload the RDP ActiveX Interop DLLs for now, we'll come back to them later.

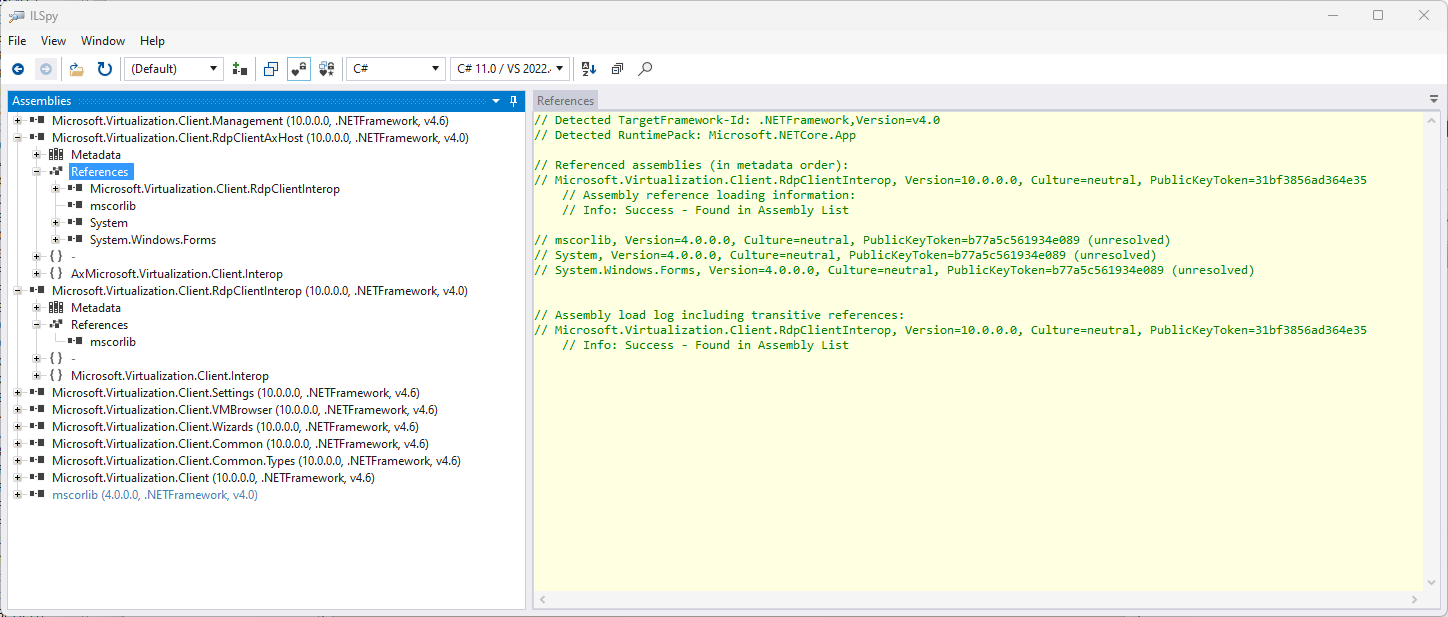

We are now down to 7 .NET assemblies in the Microsoft.Virtualization.Client namespace which we believe is what makes Hyper-V Manager tick. Inspect the assembly references to find out the interdependencies, looking for assembly that should be the easiest to rebuild from source:

Let's build a list of dependencies for each of the assemblies, considering only the Microsoft.Virtualization.Client namespace for now:

Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management.dll depends on:

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.dll

Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Settings.dll depends on:

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Wizards.dll

Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.VMBrowser.dll depends on:

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Settings.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Wizards.dll

Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Wizards.dll depends on:

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management.dll

Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.dll depends on:

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.dll

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Management.dll

Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.dll depends on:

- Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.dll

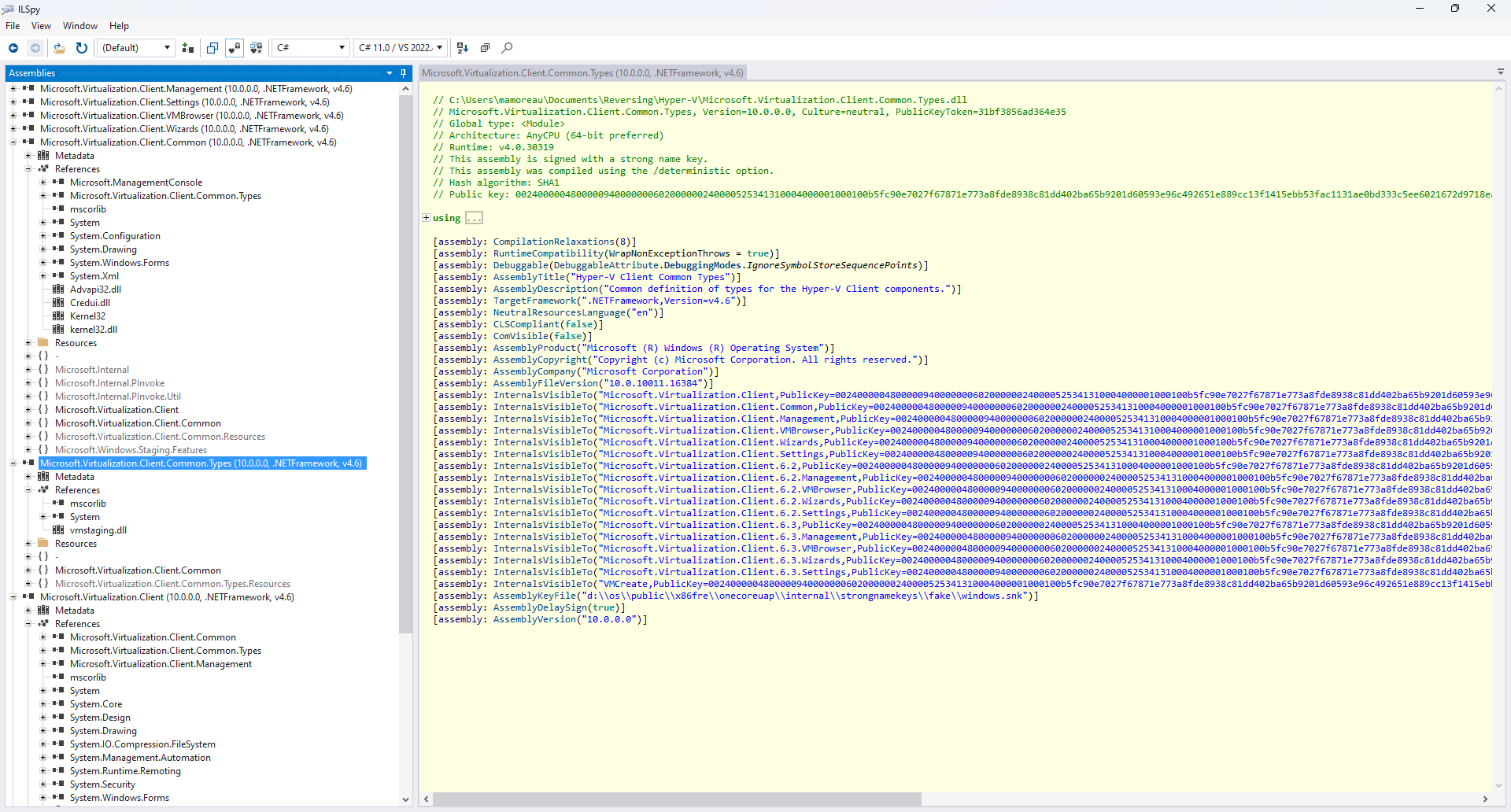

And finally, Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.dll depends on nothing except core .NET runtime assemblies, and vmstaging.dll, a native DLL found C:\Windows\System32, so the reference probably comes from pinvoke calls. This looks like our best choice to begin decompilation!

Manual Decompilation Process

One should always try manual decompilation first, just to get a feel of how far it is possible to go. However, unless the project is relatively simple, you will reach a point where you start to forget some of the steps and need to start over because you've done a risky change that needs to be reverted. Your goal with manual decompilation should be to document steps which you want to automate later. This section is only provided as a partial guide to show what it looks like, since we're going to do the full decompilation process with a script right after.

Start by creating a "Decompiled" directory, with one directory for each assembly ("Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types" for Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.dll, etc):

@('Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types',

'Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common',

'Microsoft.Virtualization.Client',

'Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management',

'Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Settings',

'Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.VMBrowser',

'Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Wizards') | % {

New-Item $_ -ItemType Directory

}

We will now go over each assembly, getting them to compile one by one according to order of dependencies, using the following steps:

- Fix internal references (project references within current solution)

- Fix external references (package references or assembly references)

- Fix AssemblyInfo.cs and broken project file (.csproj) properties

- Fix compilation issues resulting from broken or changed references

- Fix remaining issues resulting from improper decompilation output

This process is fairly repetitive, manual and error-prone. Some external assembly references may have nuget packages, some may not - you can only figure out the proper package replacement through trial and error. In the case of Hyper-V Manager, we have a few remaining assembly references directly in the Windows global assembly cache we could not get rid of in favor of a published nuget package.

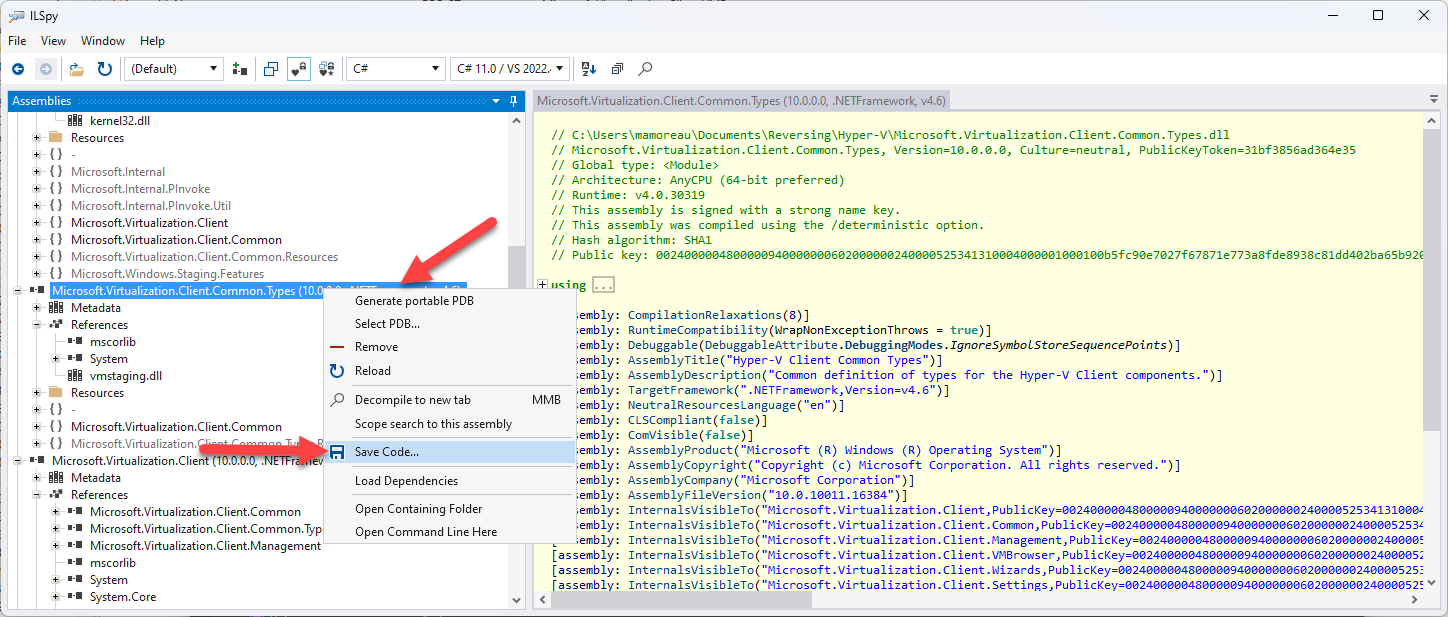

In ILSpy, right-click on the assembly, select "Save Code" then select the corresponding output directory. Repeat the process for all of the 7 Microsoft.Virtualization.Client assemblies we've identified previously:

Create a new solution file in the "Decompiled" directory, then add references to the individual project files:

dotnet new sln -n Microsoft.Virtualization.Client

Get-Item *\*.csproj | ForEach-Object { dotnet sln add (Resolve-Path $_ -Relative) }

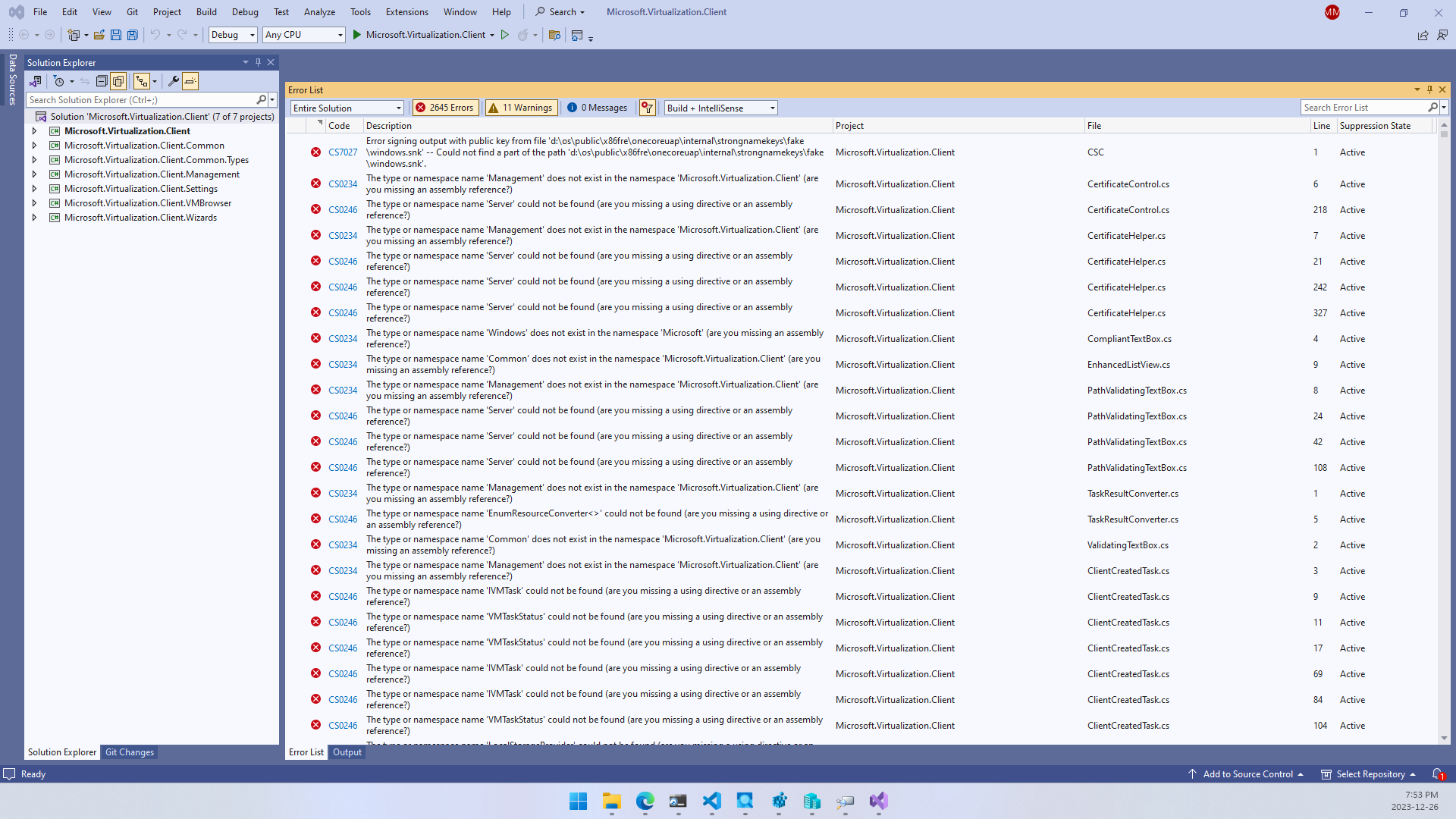

Open Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.sln in Visual Studio, then try building the solution a first time:

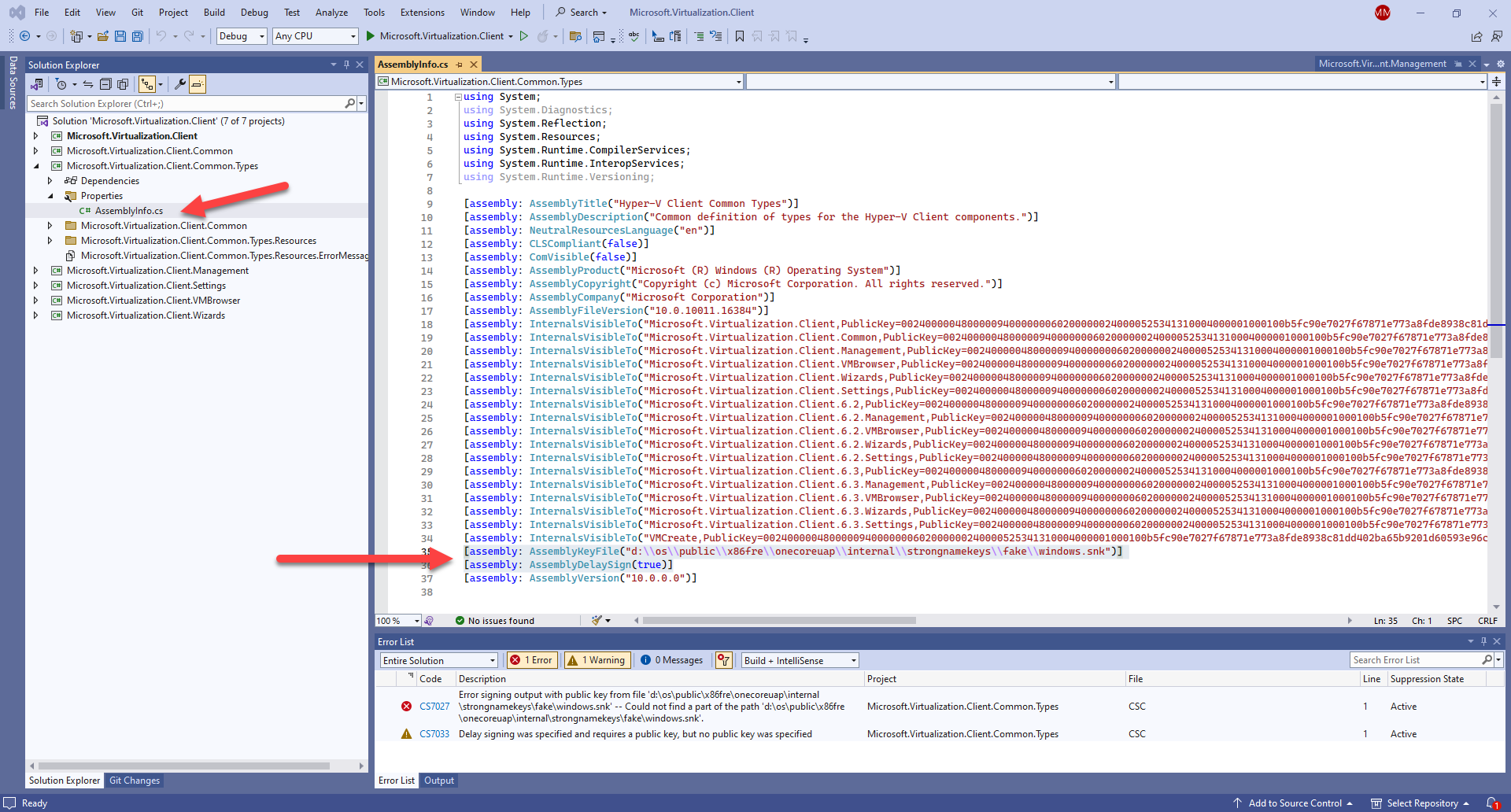

Did you really think it would be that easy? Of course not! Let's start by fixing the simplest one: assembly signing. We're not Microsoft, but ILSpy decompiled an AssemblyInfo.cs file matching the original assembly signed by Microsoft. Remove the AssemblyKeyFile and AssemblyDelaySign properties from AssemblyInfo.cs:

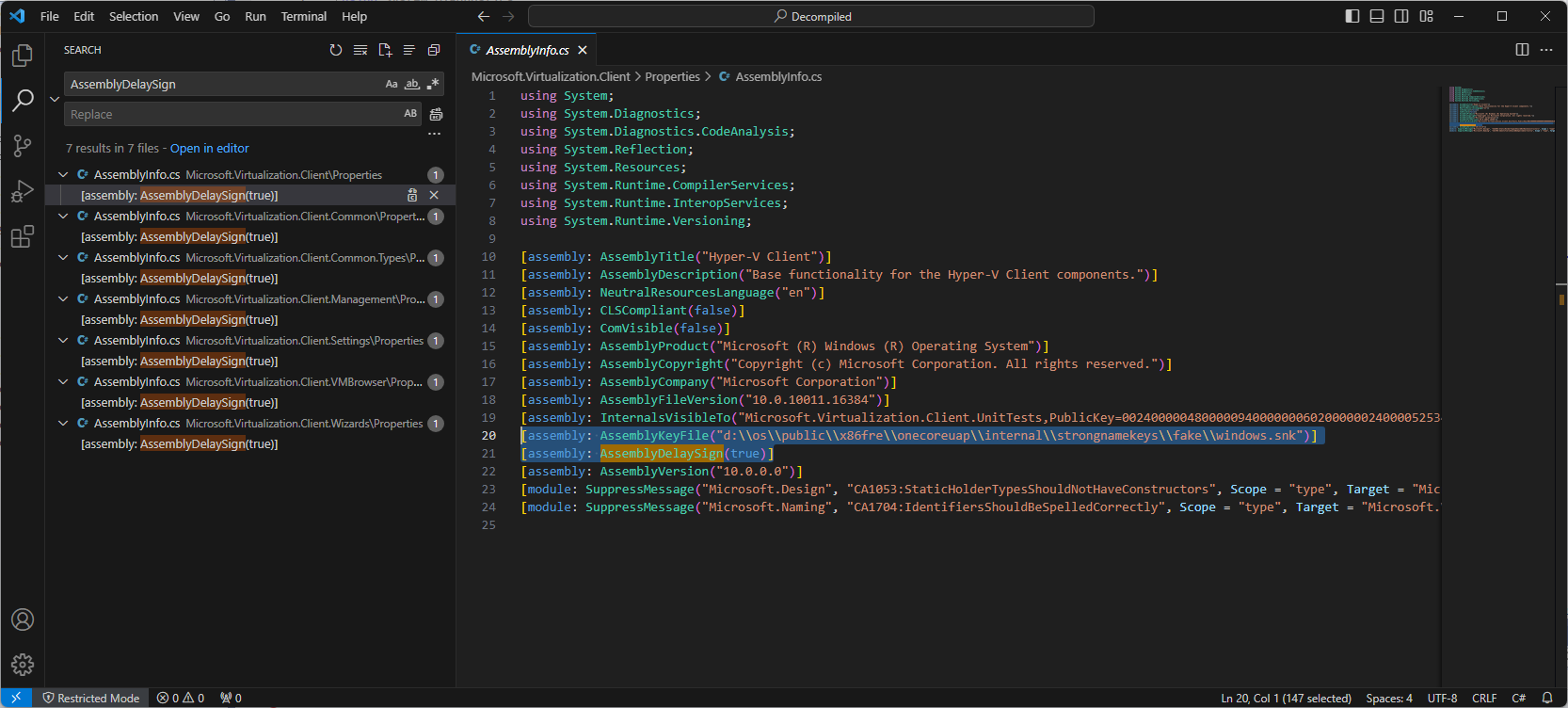

Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types should now build (yipee!) but all the other projects have the same issue. This is where using VSCode textual search can be much easier and faster than Visual Studio:

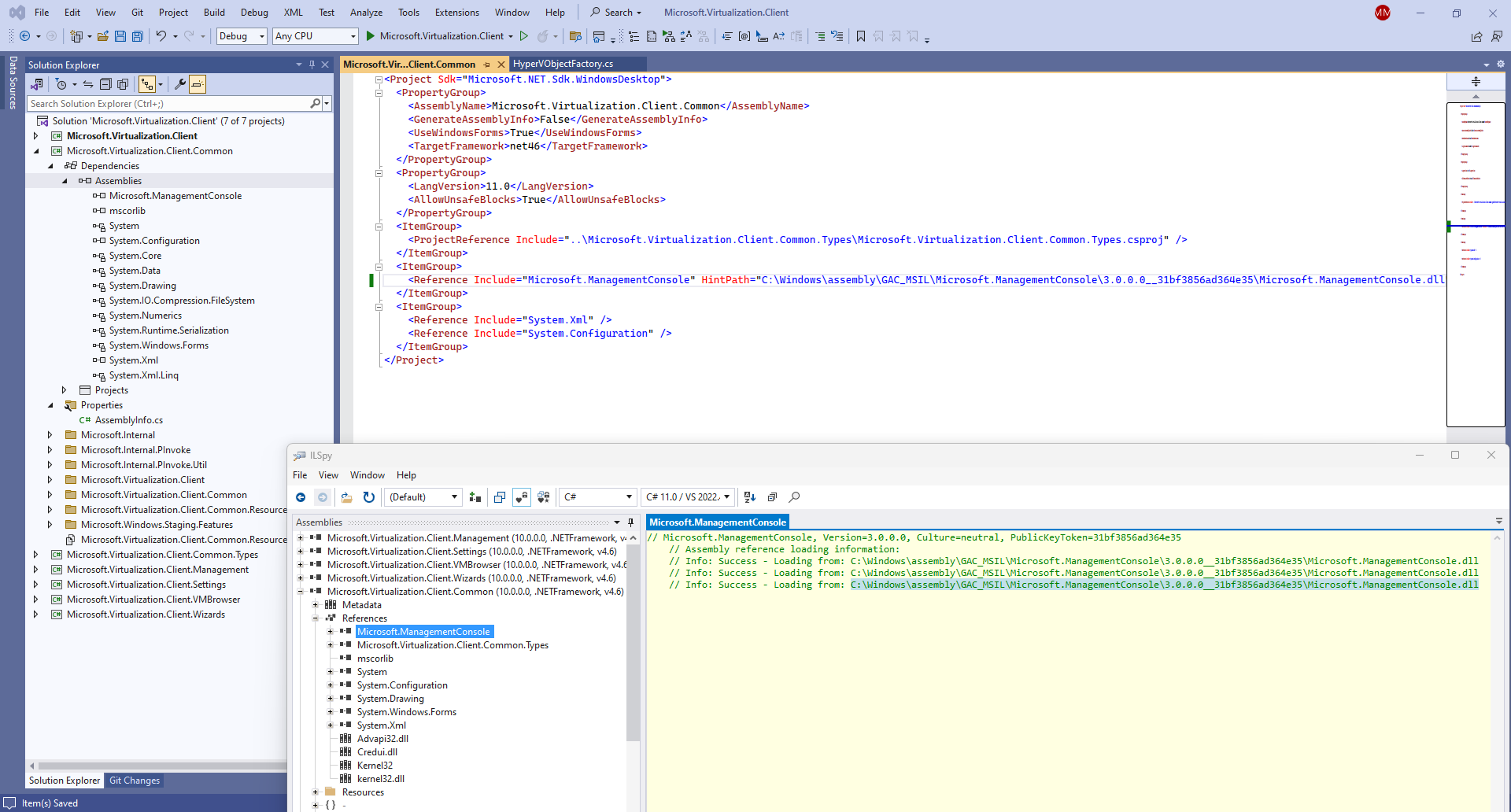

But even after fixing the assembly signing, we can't build Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common which depends on Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types. This is becauses none of the assembly and project references have been manually fixed. Add a project reference to Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types, then add an assembly reference to Microsoft.ManagementConsole.dll using the full path as shown in ILSpy:

Microsoft.ManagementConsole.dll is part of the .NET Global Assembly Cache and unfortunately, the modern .csproj format doesn't have a clean way to reference those. The most foolproof approach is to use HintPath with the full path to the assembly.

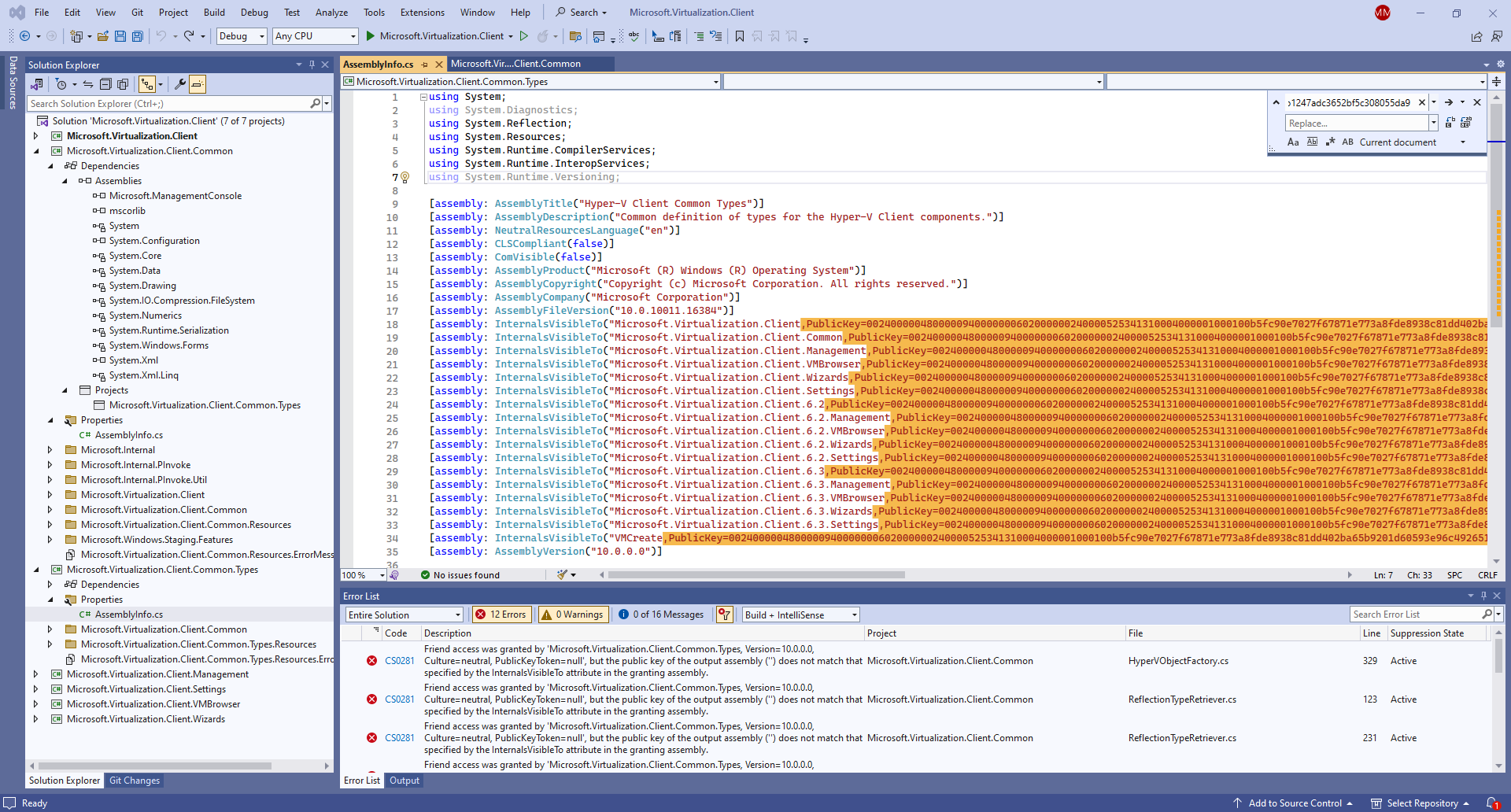

When you try building again, you'll hit errors caused by incorrect InternalsVisibleTo assembly properties in AssemblyInfo.cs. Remove the explicit PublicKey from all AssemblyInfo.cs files in the solution to fix those:

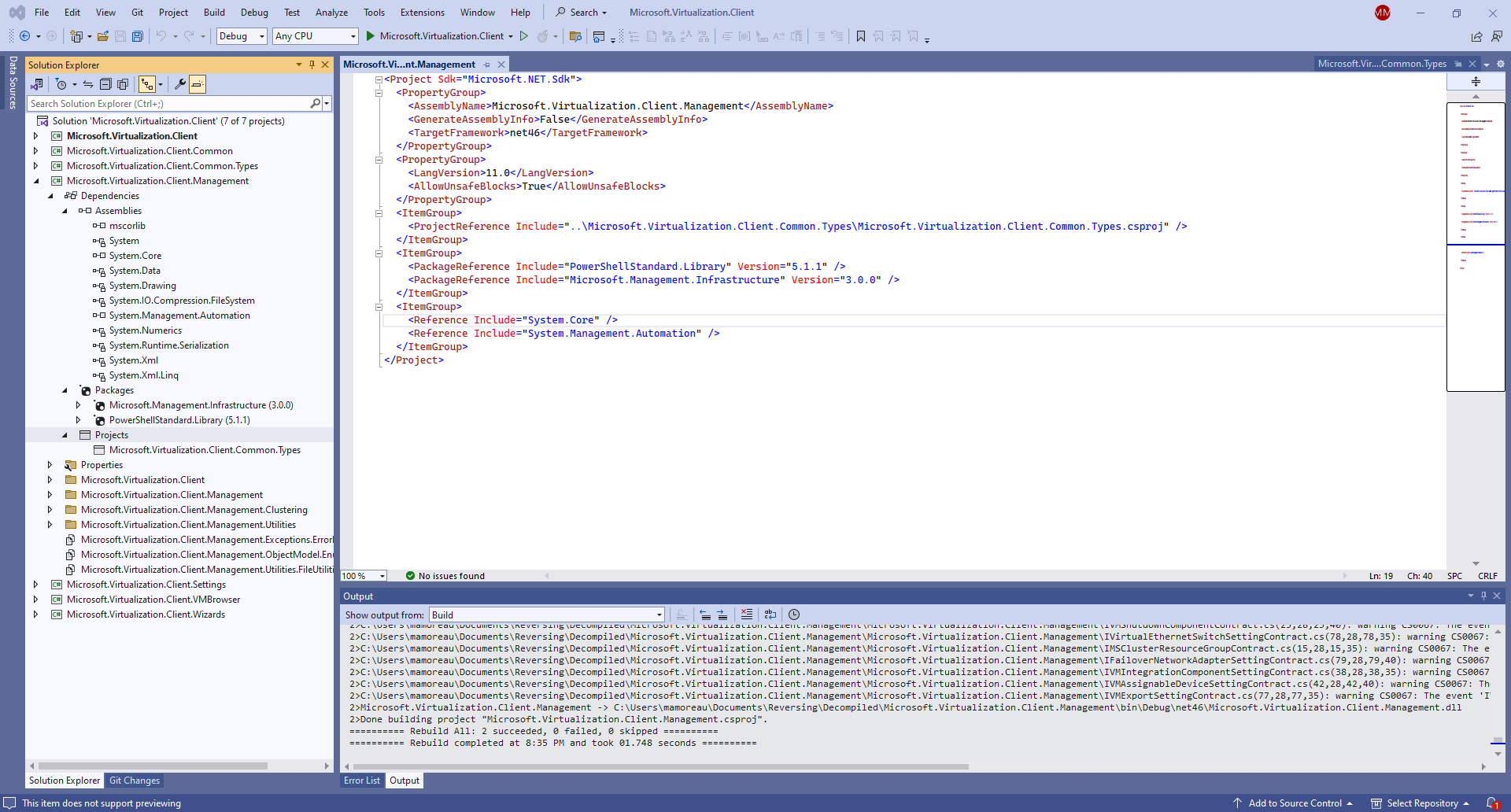

Move on to fixing Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management. Add a project reference to Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types, then add a package reference to PowerShellStandard.Library version 5.1.1 and Microsoft.Management.Infrastructure version 3.0.0:

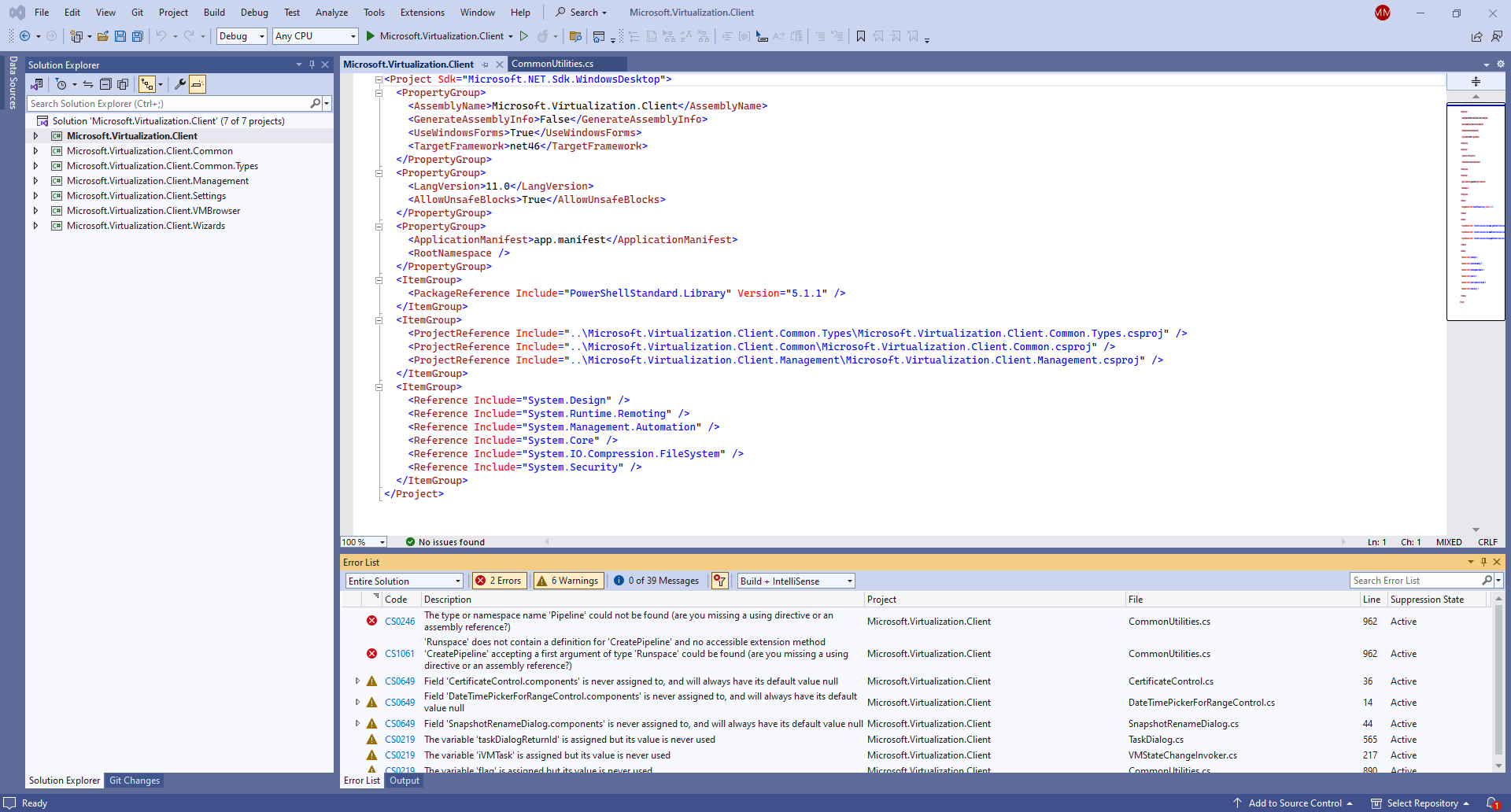

Next, fix Microsoft.Virtualization.Client. Add a project reference to Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types, Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common and Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management, then add a package reference to PowerShellStandard.Library version 5.1.1. Try building again, but this time we are not so lucky:

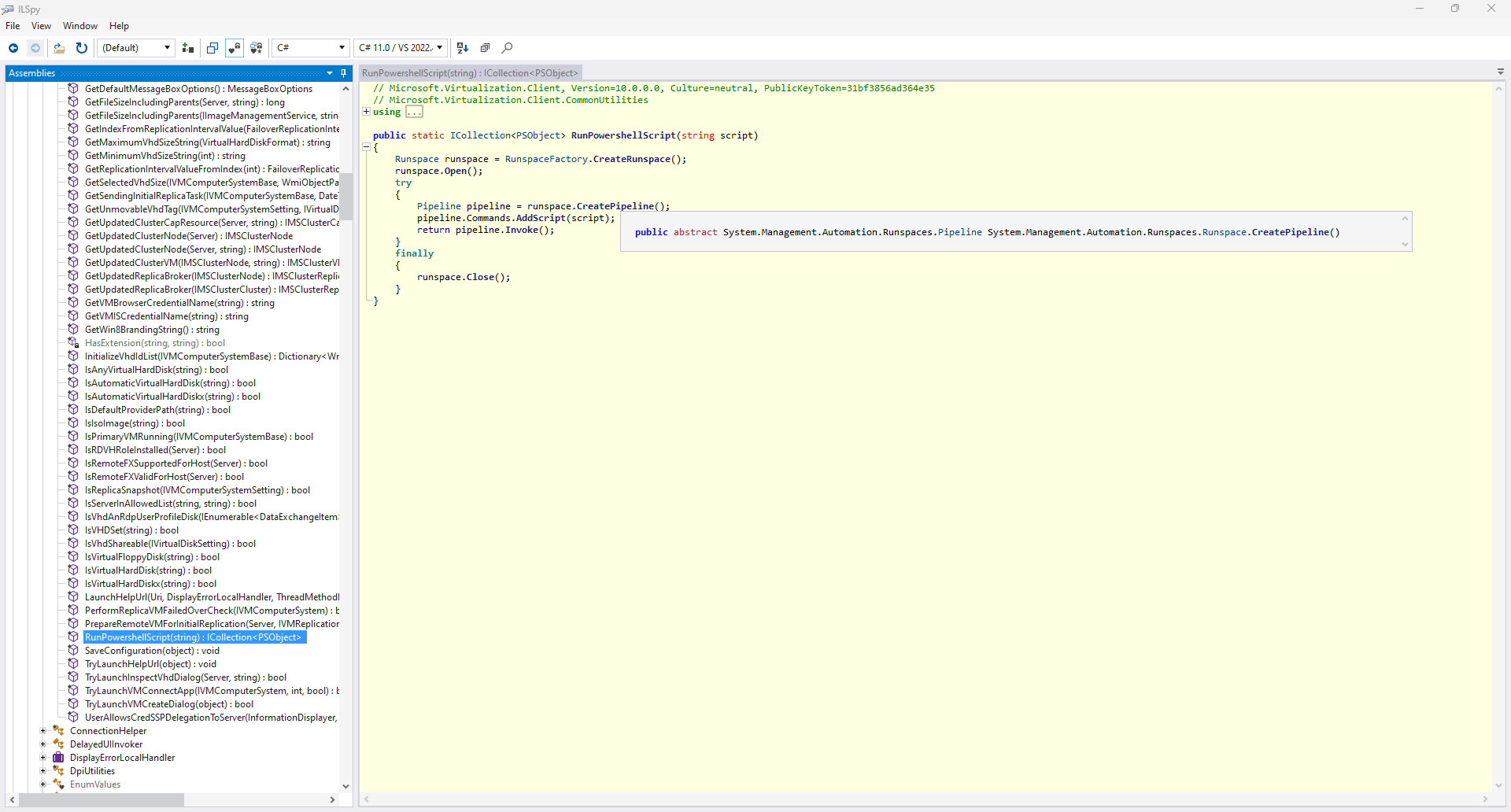

What is this "The type or namespace name 'Pipeline' could not be found" error in Microsoft.Virtualization.Client\CommonUtilities.cs? The offending code looks simple enough:

public static ICollection<PSObject> RunPowershellScript(string script)

{

Runspace runspace = RunspaceFactory.CreateRunspace();

runspace.Open();

try

{

Pipeline pipeline = runspace.CreatePipeline(); // this is what breaks the build

pipeline.Commands.AddScript(script);

return pipeline.Invoke();

}

finally

{

runspace.Close();

}

}

We take a look at the original function in ILSpy to figure out where the Pipeline type is coming from:

Weird, is it coming from System.Management.Automation, the PowerShell SDK. We've replaced the previous assembly reference with a package reference to PowerShellStandard.Library and somehow the original code was so old it used a type that's been moved elsewhere. Let's patch this function such that it can build again:

public static ICollection<PSObject> RunPowershellScript(string script)

{

Runspace runspace = RunspaceFactory.CreateRunspace();

runspace.Open();

try

{

System.Management.Automation.PowerShell powerShell = System.Management.Automation.PowerShell.Create();

powerShell.Runspace = runspace;

powerShell.AddScript(script);

return powerShell.Invoke();

}

finally

{

runspace.Close();

}

}

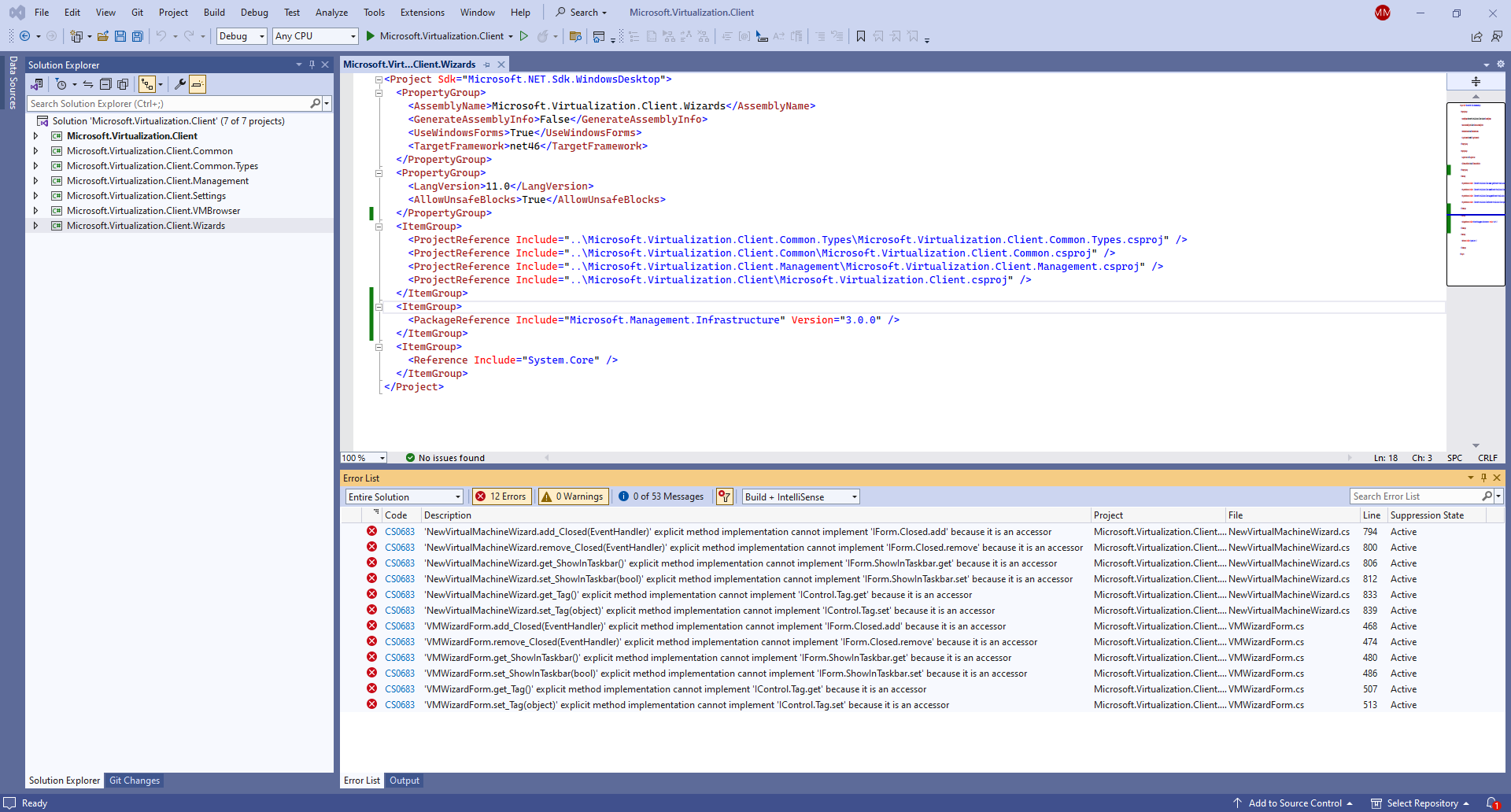

And it builds! Next is Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Wizards. As usual, let's start by fixing the assembly references to then try building:

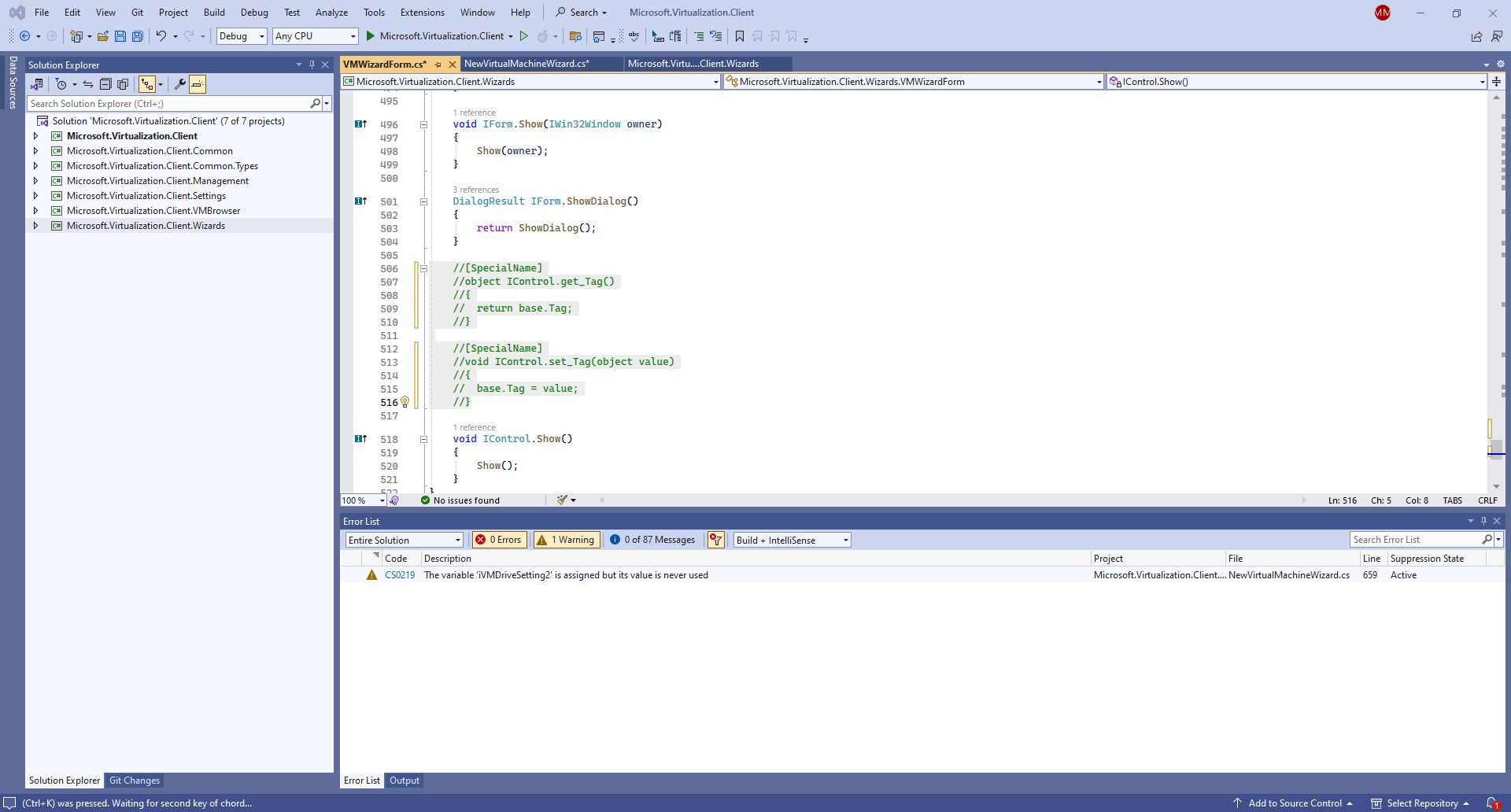

No luck this time! We seem to be hitting problems due to automatic decompilations of accessor functions that look like default implementations. Maybe those shouldn't even be decompiled, so let's comment them out:

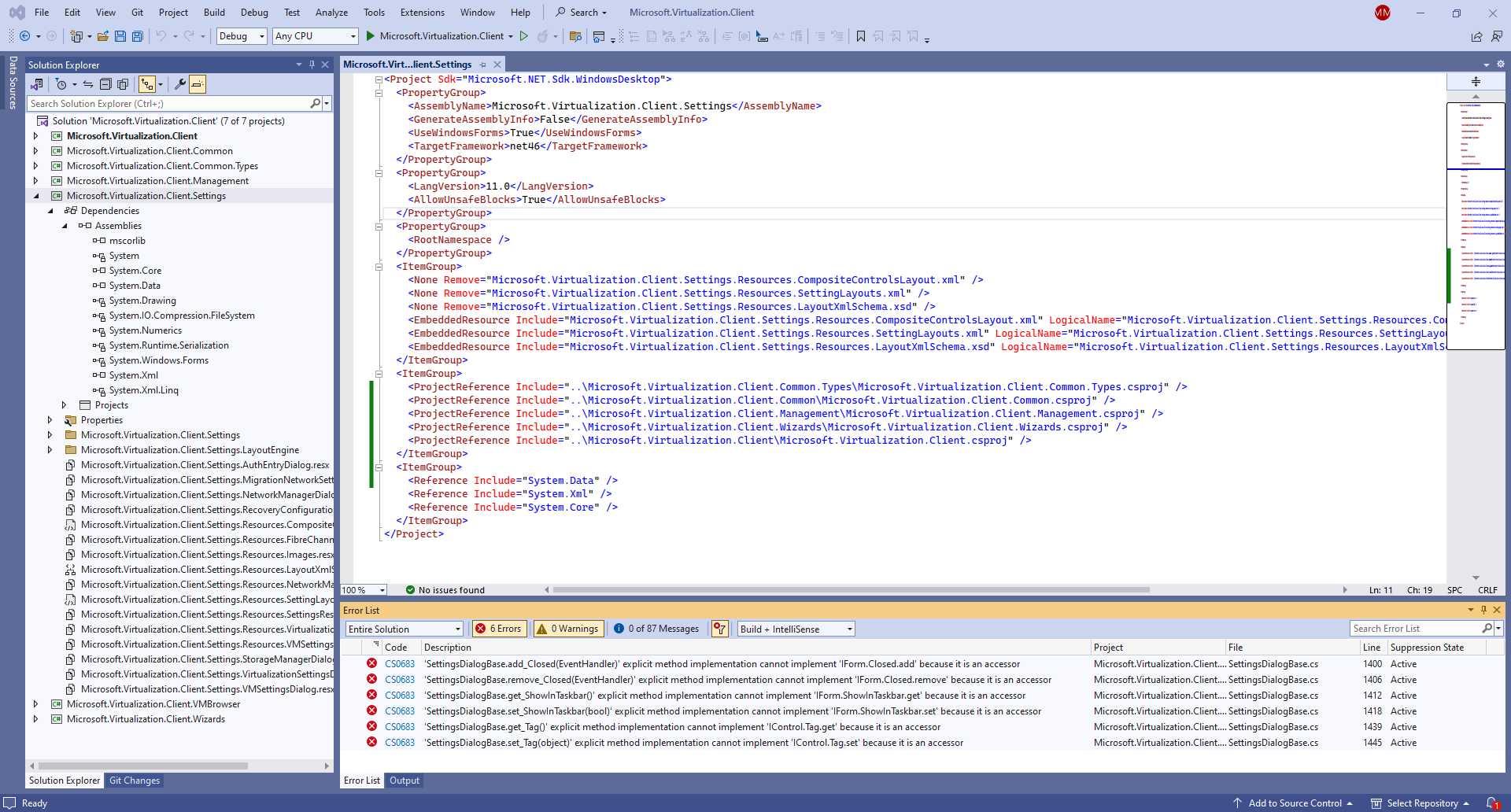

And success, it builds! Now fix Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Settings assembly references, and comment out similar accessor functions that break the build:

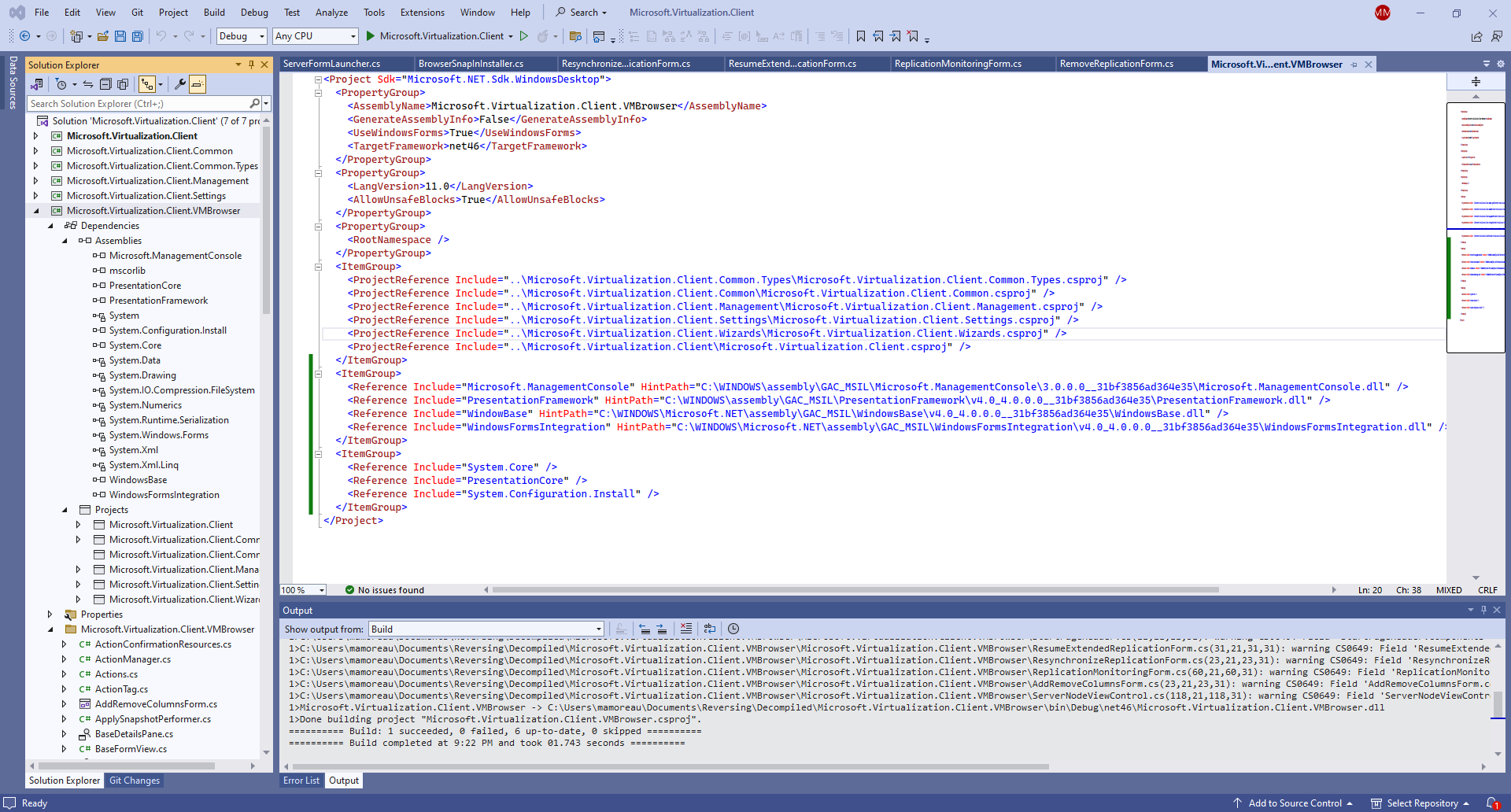

We're down to the last one: Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.VMBrowser. Fix the assembly references:

<ItemGroup>

<ProjectReference Include="..\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.Types.csproj" />

<ProjectReference Include="..\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Common.csproj" />

<ProjectReference Include="..\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Management.csproj" />

<ProjectReference Include="..\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Settings\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Settings.csproj" />

<ProjectReference Include="..\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Wizards\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.Wizards.csproj" />

<ProjectReference Include="..\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client\Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.csproj" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Reference Include="Microsoft.ManagementConsole" HintPath="C:\WINDOWS\assembly\GAC_MSIL\Microsoft.ManagementConsole\3.0.0.0__31bf3856ad364e35\Microsoft.ManagementConsole.dll" />

<Reference Include="PresentationFramework" HintPath="C:\WINDOWS\assembly\GAC_MSIL\PresentationFramework\v4.0_4.0.0.0__31bf3856ad364e35\PresentationFramework.dll" />

<Reference Include="WindowBase" HintPath="C:\WINDOWS\Microsoft.NET\assembly\GAC_MSIL\WindowsBase\v4.0_4.0.0.0__31bf3856ad364e35\WindowsBase.dll" />

<Reference Include="WindowsFormsIntegration" HintPath="C:\WINDOWS\Microsoft.NET\assembly\GAC_MSIL\WindowsFormsIntegration\v4.0_4.0.0.0__31bf3856ad364e35\WindowsFormsIntegration.dll" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Reference Include="System.Core" />

<Reference Include="PresentationCore" />

<Reference Include="System.Configuration.Install" />

</ItemGroup>

Then comment out the accessor functions that cause problems (there are a lot more of them, unfortunately). Try building the entire solution this time:

Success! Finally, all 7 assemblies of interest can now be built from source. Are we done yet? Well... we still have to find a way to run our modified Hyper-V Manager, and once we do, we'll run into a lot of issues with satellite resource assemblies. You know, the assemblies in that 'en-US' directory that we've conveniently ignored at the beginning.

Automated Decompilation Process

Leave the manually-compiled project aside, and clone my Hyper-V Manager automated decompilation project git repository:

git clone git@github.com:awakecoding/hyper-v-manager.git

Open a PowerShell 7 terminal, then run the bootstrap.ps1 script:

.\bootstrap.ps1

If everything went well, you should now have a "Decompiled" directory with a "Microsoft.Virtualization.Client.sln" solution file you can now open and build in Visual Studio:

Well, that was too almost easy, wasn't it? Keep in mind that some additional post-compilation fixes may be required due to changes in either the original assemblies or the way ILSpy decompiles them in the future. However, at the time of writing this blog post, everything builds properly.

That's why automation works better in the end: too many times I have failed to achieve success because I could only get halfway, and then forgot most of the steps by the time I could give it another go. If you structure your decompilation project with a script that deletes the "Decompiled" directory to start over from scratch, automating the steps you've discovered work through manual decompilation, it becomes much easier to make incremental progress.

Let's go over the major differences of what the bootstrap.ps1 script does differently:

- Copy assemblies of interest in local "Assemblies" directory

- Use AssemblyInfo.cs files generated from .csproj properties

- All .csproj files now include a common build property file

- Use "overlay" project files that overwrite the decompiled ones

- Call ilspycmd from PowerShell to decompile assemblies automatically

- Decompile satellite resource assemblies located in 'en-US' directory

- Rename decompiled .resx files to remove assembly prefix from file names

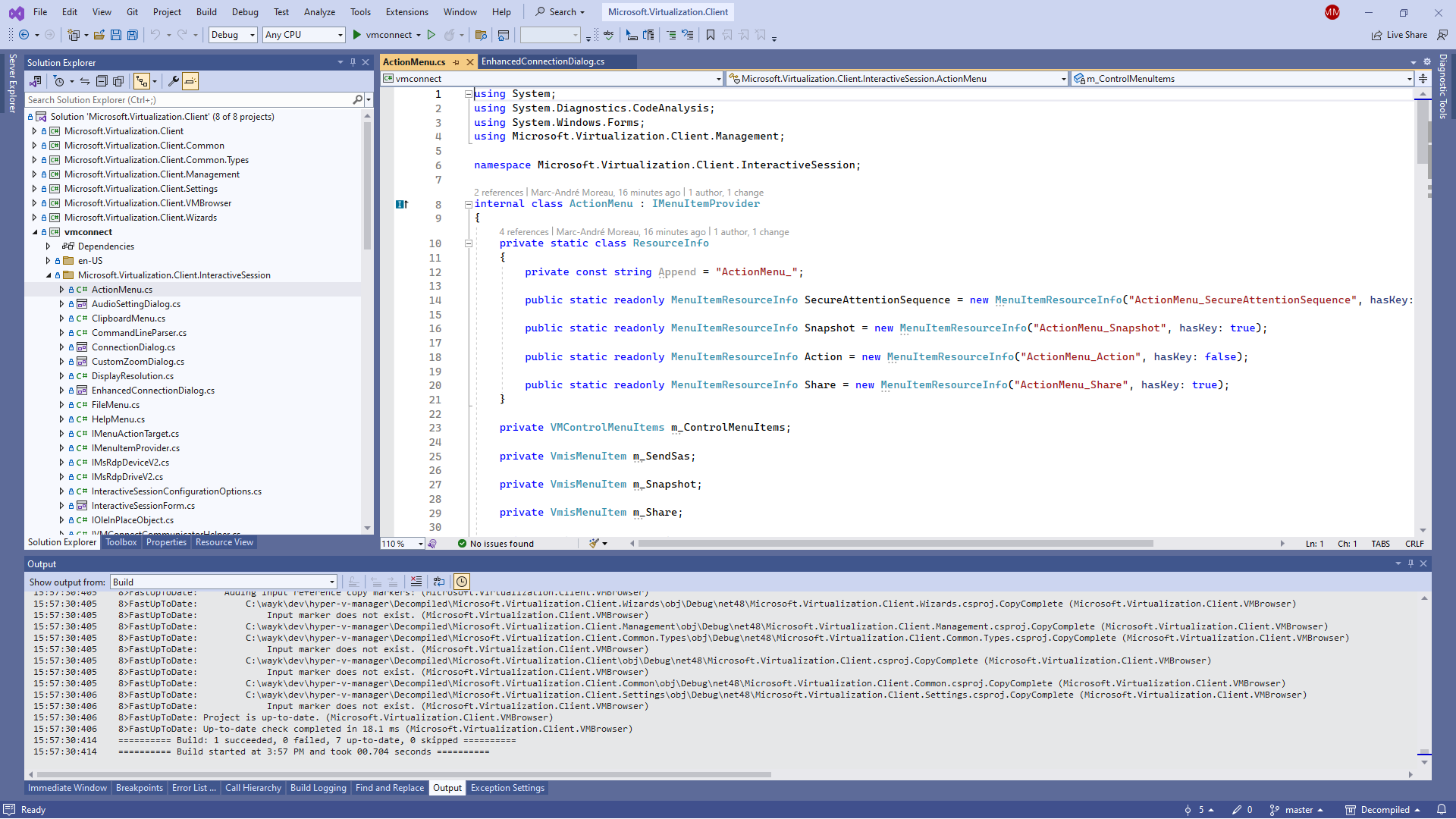

- Decompile vmconnect.exe and fix it, something we've skipped earlier

- Patch executable path detection to use the same directory as the assemblies

- Apply many more post-decompilation fixups for all kinds of additional issues

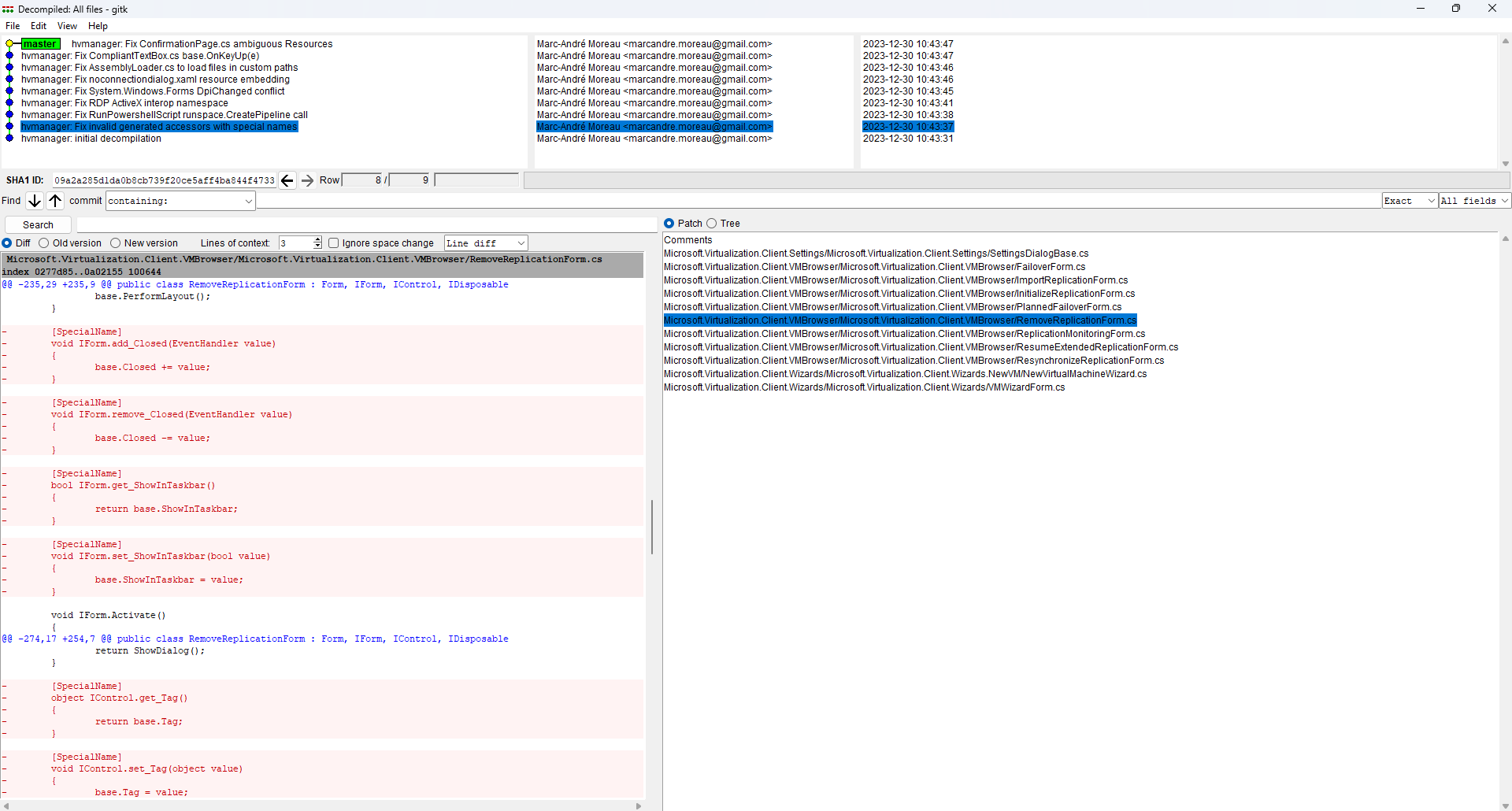

Take the time to look at the script for yourself to study what it does. One important thing you'll notice is that it creates a local git repository from the "Decompiled" directory, and individual commits for all the automated changes done to the code after initial decompilation. You may wonder why bother creating a git repository for something that isn't going to be published: git commits make it very easy to track changes at every step of the way, and revert them if needed:

Running recompiled Hyper-V Manager

Create the "C:\Hyper-V\Manager" directory, copy the build output there, then copy hvmanager.msc to the same directory. Import hvmanager.reg to register the MMC component with a different GUID than the original Hyper-V Manager, and point it to "C:\Hyper-V\Manager" as the install path.

You can now try launch mmc.exe with hvmanager.msc:

mmc.exe "C:\Hyper-V\Manager\hvmanager.msc"

Alternatively, you can launch mmc.exe as the current user and avoid the UAC prompt, which can come in handy if you want to debug your recompiled project in Visual Studio without launching it as an administrator:

$Env:__COMPAT_LAYER='RunAsInvoker'

mmc.exe "C:\Hyper-V\Manager\hvmanager.msc"

However, this trick requires you to become part of the local Hyper-V Administrators, otherwise you won't be able to manage VMs:

$CurrentUser = [System.Security.Principal.WindowsIdentity]::GetCurrent().Name

if (-Not (Get-LocalGroupMember -Group "Hyper-V Administrators" -Member $CurrentUser -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue)) {

Add-LocalGroupMember -Group "Hyper-V Administrators" -Member @($CurrentUser)

}

You can now create a shortcut on the desktop with C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /c "SET __COMPAT_LAYER=RunAsInvoker & START mmc.exe "C:\Hyper-V\Manager\hvmanager.msc"" as the target, and %ProgramFiles%\Hyper-V\SnapInAbout.dll for the Hyper-V Manager icon. Once the shortcut is created, you can drag it onto the taskbar, and delete the original shortcut if you don't want it on the desktop:

![]()

Last but not least, use the new shortcut to launch your custom Hyper-V Manager build, then use Process Explorer (procexp) to confirm that the .NET assemblies loaded are the ones we expect in C:\Hyper-V\Manager:

If it's not using cached assemblies, but really loading the assemblies we've just build from source, then congratulations! It works! You can now start patching Hyper-V Manager to fix some of the things that annoy you the most.

Closing Thoughts

Even if we've managed to rebuild and patch Hyper-V Manager from source, this is not enough for a real community project to take place. As much as I would like to just upload the decompiled source code to GitHub to start making significant changes to it, there's no legal standing for this project. I can only go as far as streamlining the process of decompilation such that others can experiment making changes locally.

Are you a Hyper-V Manager user? Do you wish it could be improved? Make yourself heard, and help save Hyper-V Manager by convincing Microsoft to open source it!